Blindsided

By Deborah Dills It’s been 6 years since I got the news over the phone late one night from my brother David. He told me to sit down because he had something shocking to tell me. I thought it was about our dad, Abe, who was in the hospital due to severe dementia and a fall two weeks earlier, but David said it was something else. He’d been cleaning Abe’s New York apartment and found a metal box with a lock on it. When he opened it, he found documents pertaining to my European adoption—an adoption I never knew had happened.

It’s been 6 years since I got the news over the phone late one night from my brother David. He told me to sit down because he had something shocking to tell me. I thought it was about our dad, Abe, who was in the hospital due to severe dementia and a fall two weeks earlier, but David said it was something else. He’d been cleaning Abe’s New York apartment and found a metal box with a lock on it. When he opened it, he found documents pertaining to my European adoption—an adoption I never knew had happened.

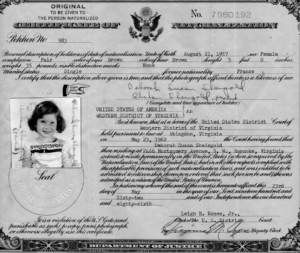

Stunned and blindsided, he read from the documents. I’d been born in Baumholder, Germany to a Jewish woman from Strasbourg, France and was adopted at 3 months old. Half of my adoption documents were in German and half in French with English translations.

I’d always known I’d been born in Germany because the woman I now know to be my adoptive mother, Norma, told me she and Abe, who was a Jewish chaplain in Chateauroux, France, had been sightseeing in Germany when she had me. Now I know the truth was that they went to Germany from France to adopt me.

In the courts in France, Norma and Abe changed my birth name, Darlene Barbara, to Deborah Susan, or Devorah Shoshana in Hebrew—a name they deemed more appropriate for a Jewish girl and the daughter of a reform rabbi.

After learning about this, I began a search to find out all I could about my birthmother and took two DNA tests. I had a close match to a woman named Jeanette who happened to be a Jewish genealogist by profession and who said she’d do all she could to help me learn about my mother, Jenny Helene Levy. Jeanette had a friend in Belgium who spoke French, and she obtained my mother’s birth certificate in Strasbourg. It revealed that she’d been born in 1921 to Samuel Levy and Hedwig Jülich Levy, so I was able to know what my grandparents’ names were.

I also discovered that Jenny came into the US in 1958, but left in 1988 to emigrate to Israel. Through another DNA test I found another cousin in Paris who in turn found a relative in Israel who took care of my mother during her later years. They sent me a memoir she’d written late in life that told the story of having fled Nazi-occupied Europe on foot, walking with a guide across the Pyrenees Mountains from France to Spain with only a paper bag containing a banana and her underwear. She remained in Spain until the end of the war. Her father, Samuel, died of a heart attack in 1942, possibly due to having lost his shipping business in Strasbourg to the Nazi laws against Jews. Her mother, Hedwig, went into hiding. Around 1959, she joined her sister in the United States and later returned to Nancy, France and died there in 1973.

I learned that most of my Jewish birth family escaped Nazi Germany, but seven who did not perished in concentration camps such as Auschwitz, Chelmno, and Theresiendstadt.

I also found a first cousin with Jeanette’s help, the son of Jenny Levy’s brother—my uncle Joseph—who was born in Strasbourg in 1913. He told me his father had been a spy in the French military during the war, and after his escape to the US with his wife, Ginette, he changed his name so he could return to France and not be arrested for having abandoned his post. My cousin told me Jenny told his parents, who lived in the US, that she gave birth to a baby girl in Baumholder in 1957, but that that baby—me—had died of a disease. Other family members in Europe were told that I had died in a hot car.

My birthfather had not been listed on my birth certificate or my adoption papers. I turned to the Facebook group DNA Detectives for assistance, and a search angel helped me discover that my birthfather was an American GI. And that same day I found out I had a biological sister, Charlene, born after me in the US, but adopted by our birthfather’s sister and husband. Sadly, she died in 1989, so I was never able to reunite with her. I did, however, discover that I had a half sister who lives in Virginia, and we speak often.

To learn all this at age 57 rocked my world. The tragedy is that I never got to meet either of my birthparents or my sister, so my heart is broken in half. By the time I learned this, both my biological parents were deceased. The pain of this more than 50-year old secret remains with me today—not only the pain caused by my adoptive parents not telling me, but also from finding out all their relatives knew I had been adopted. Looking back, I see I didn’t fit it to their family. I didn’t get along with my adoptive mother and I continually ran away when I was a teenager, finally for good in 1979, when I joined the Navy to get away from her constant abuse. I ask myself every day, why? Why didn’t my parents tell me I was adopted? What were they afraid of? I often cry buckets of tears over the pain of my secret adoption story and feel so cheated at not knowing my birth relatives growing up. But I continue my search daily to find out more about my birth family which, at times, makes me smile.Deborah Dills lives in Humble, Texas with her two sons, Aaron and Brian; a dog named Stanley; and a Tuxedo cat named Roman. She served in the Navy on active duty from 1979 until 1991 and in the Naval Reserves. She spent time living in Israel on Kibbutz Ruhama in the Negev. She loves gardening, cooking, and decorating; works on genealogy research every day; and is overjoyed to have found relatives living in many countries beyond the US, including France, Germany, Switzerland, and Peru. Find her on Facebook.BEFORE YOU GO…

Look on our home page for more articles about NPEs, adoptees, and genetic genealogy.

- Please leave a comment below and share your thoughts.

- Let us know what you want to see in Severance. Send a message to bkjax@icloud.com.

- Tell us your stories. See guidelines.

- If you’re an NPE, adoptee, or donor conceived person; a sibling of someone in one of these groups; or a helping professional (for example, a therapist or genetic genealogist) you’re welcome to join our private Facebook group.

- Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @Severancemag.