By Ari Spectorman

March 23, 2022 was our final day for the winter season at our home in Key West. The SUV was fully packed for the long ride home to New Hope, PA. My husband, Tony, and I biked over for one last dinner at El Siboney, a favorite Cuban joint a few blocks away. During dinner I went to the rest room and urinated nothing but blood. “This can’t be good,” I thought.

We quickly biked back home. Perhaps it was a kidney stone? There were no previous symptoms of any kind. But soon there was intense, painful pressure and I could not urinate at all. We rushed to urgent care in Key West. A quick CT scan revealed a mass in my left kidney. I needed a catheter inserted right away to release the pressure and was sent to South Miami by ambulance, a 3-½ hour slog. Tony followed soon after in the already packed SUV. I was frightened and worried Tony would be overwhelmed.

I spent a week in a South Miami hospital trying to clear all the blood clots through my catheter, while undergoing various tests and scans. The devastating news was not only a most likely kidney cancer diagnosis, but also the appearance of a suspicious nodule on my pancreas. We flew back home and arranged for a transport company to collect and ship the loaded SUV to us. We would pursue further diagnostic testing and a course of action once we were settled in our New Hope home.

An endoscopic needle biopsy at the pancreas confirmed our worst fears, metastatic kidney cancer. (Stage four, advanced, and metastatic all mean the same thing: a cancer that has spread beyond the original location.) I had a suspicious nodule in my lungs, two more in my peritoneum (a membrane in the abdominal cavity), and two on the pancreas. Three weeks later, on April 21, my left kidney was surgically removed at Doylestown Hospital.

I’ve always known I was adopted; it was not a secret. My adoptive mother, who only recently passed at age 90, always encouraged me to find information regarding my biological parents. Many years ago, I contacted the Louise Wise adoption agency and was told my young Jewish mother gave no information regarding the father, only that it was a single encounter. At the time of my birth, in September 1961, she had asked not to be contacted, so my records were sealed. I was not particularly motivated to look for my birth parents for most of my life. Unlike many other adoptees, I never felt incomplete, and it just never felt terribly important to me. I had a full life. Married when legally permitted in 2013, Tony and I first met in 1979 as freshmen at our university. We owned a Greenwich Village restaurant together, bought a home in Bucks County, PA, and later, I grew a successful financial advisory business over a 26-year period.

Eventually I did get around to thinking about my origins. I always thought my birth father was not Jewish—I have a tiny button nose and a somewhat darker complexion—maybe my father was from some exotic background? That would be interesting. In 2019, I joined 23andMe on a lark. 99.9% Ashkenazi Jew— boring! But no immediate relatives. Some months later suddenly a half-sister appeared using only the initials NF, from Morristown, NJ. She was born in 1958 and was also adopted via the Louise Wise Agency. She was looking for information about her family. I immediately wrote to her introducing myself. “I assume we share the same mother! I’m Ari Spectorman, from New Hope PA, who are you?” Within a week, not only had she not replied, but she removed all traces of herself from the 23anMe site. I scared her away, I guess. Perhaps because I’m gay and she is very religious? Being ghosted like this invites much speculation.

In the post-surgery recovery room, I checked my email. A first cousin newly discovered via 23andMe wrote me to reveal one of her two living uncles is my biological father. A complete shock, and the timing was beyond belief.

While recovering from surgery, I awaited more news on my suddenly new biological family. A few cousins joined the 23andMe site to find out which family had a new half-brother. Meanwhile, I had to decide a treatment plan and I was busy getting my financial affairs in order. We decided to sell our Key West home. It sold in one day to buyers who wanted all our furnishings, down to every sheet, towel, dish and all décor. A friend removed a few personal items and some of Tony’s favorites of his own artwork. We closed on the sale without ever returning there. Tony and I are able to make important decisions quickly and we tend not to second guess ourselves. I sold my asset management and financial advice firm to my junior partner, executing a previously drawn buy/sell agreement. I would now be retired, and able to focus my energy full time on my health.

My local oncologist recommended a standard immunotherapy and chemo regimen, but I wanted to find other options. I read 75 kidney cancer trial summaries looking for one that fit me, and after an exhausting search I found one at UPenn in Philadelphia willing to enroll me pending brain and bone scans. Tony and I would need to drive the hour to the hospital every 14 days for an investigational infusion during a 2-year trial period. I would also begin the standard treatment at the same time. During the week of my additional scans, on May 8, I received the news from one of my new cousins—my father is Larry Bell, retired Cleveland corporate lawyer, age 86. I have three new half-sisters, Jessica, Liz, and Sarah. We saw some resemblance in their photos. Excited and overwhelmed, I didn’t know what to think beyond a feeling of “how nice this is.”

I was cleared for participation, my clinical trial got underway, and our new routine began. Whenever possible, Tony and I would travel to interesting places in the 14-day period between treatments. My side effects were best described as annoying but manageable, until October, when I developed permanent type 1 autoimmune diabetes, which occurs in 1% to 2% of immunotherapy patients. We flew to Cleveland to meet Larry and his family.

Larry, Jessica, Sarah, and Liz

Larry has mild to moderate cognitive impairment, so I did not get to know him when he was most vital and literate. He has no memory of a “date” in January of 1961—and why would he? We assumed he never found out the young woman was pregnant; she probably hid her pregnancy until she had to be sent away for the duration. The month I was born, September 1961, Larry met his future wife, Nancy. They raised their three daughters in Shaker Heights, Ohio, an affluent, bucolic suburb of Cleveland. By all accounts Larry was a brilliant attorney and read voraciously, a habit which, apparently, I inherited from him. All three Bell daughters are intelligent, warm, and empathetic. It’s a delight to get to know them. The eldest daughter, Jessica, also has three daughters, and I’m getting to know my new nieces as well. It feels like I’ve found my tribe, after a lifetime detour.

Meanwhile, periodic scans showed no growth in my tumors since the start of treatment, with some mild shrinkage. Shortly after the Cleveland visit, however, an unrelated spinal stenosis issue led to an MRI that inadvertently turned up a suspicious area in my prostate. Sure enough, I had an aggressive form of prostate cancer that required surgical removal. By all accounts totally unrelated to my kidney cancer, just dumb luck. I even had extensive DNA testing performed to see if I had any known genetic predisposition for cancer—and no, I do not. So now I was dealing with managing my ongoing treatments, learning how to live with type 1 diabetes, and the bladder incontinence and erectile dysfunction that accompanies most all prostate surgeries.

As the months went by, my new family wanted more details about my birth mother. They wanted the whole story, and their hunger for information finally prompted me to try again to find out who my birth mother was. I had a vague memory that New York had changed a law regarding adoption, but I never pursued it. Now I was prepared to follow the leads. Louise Wise Adoption Services, which was the premier Jewish adoption agency for decades, folded in 2004. It is indeed the same agency that in 1961 placed three identical triplets in separate households as part of an infamous “scientific study.” A widely seen documentary was made about this titled Three Identical Strangers (2018.) I had an older adopted brother, who had been abandoned as an infant before placement by Louise Wise with my parents. After three months he clearly had developmental difficulties. The agency offered to take him back and replace him with a perfect baby, as if he were defective merchandise. My parents said no and kept him.

After a bit of online sleuthing, I found out I could get a copy of my sealed pre-adoption birth certificate for $15 plus a shipping fee from the NYC department of Health, just like that. (The new “equal rights for adoptees” law in New York went into effect in 2020.) The website said it could take up to ten weeks to receive the overnight UPS envelope. It arrived in four days.

The birth certificate listed my mother as Miriam G Katz, age 23, residence at 77 Chicago Avenue, Staten Island, New York. No father listed as expected. My name was given as (Male) Katz. A common Jewish name, what next? A smart friend looked at that Staten Island address using Google Maps in terrain view. “77 Chicago Avenue looks too large a building to be a single-family home; it looks more like an office building.” A few clicks later we found it:

The Staten Island Home for Unwed Jewish Mothers.

So, it wasn’t her actual home; she gave the address where she was sent to live for during her pregnancy. I called Jewish Services, the surviving parent organization, but their legal department said they have no records going back that far.

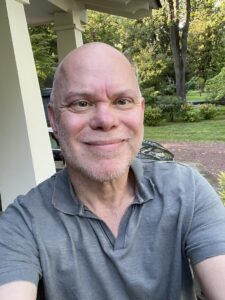

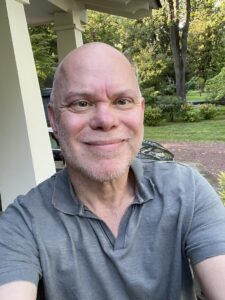

Ari

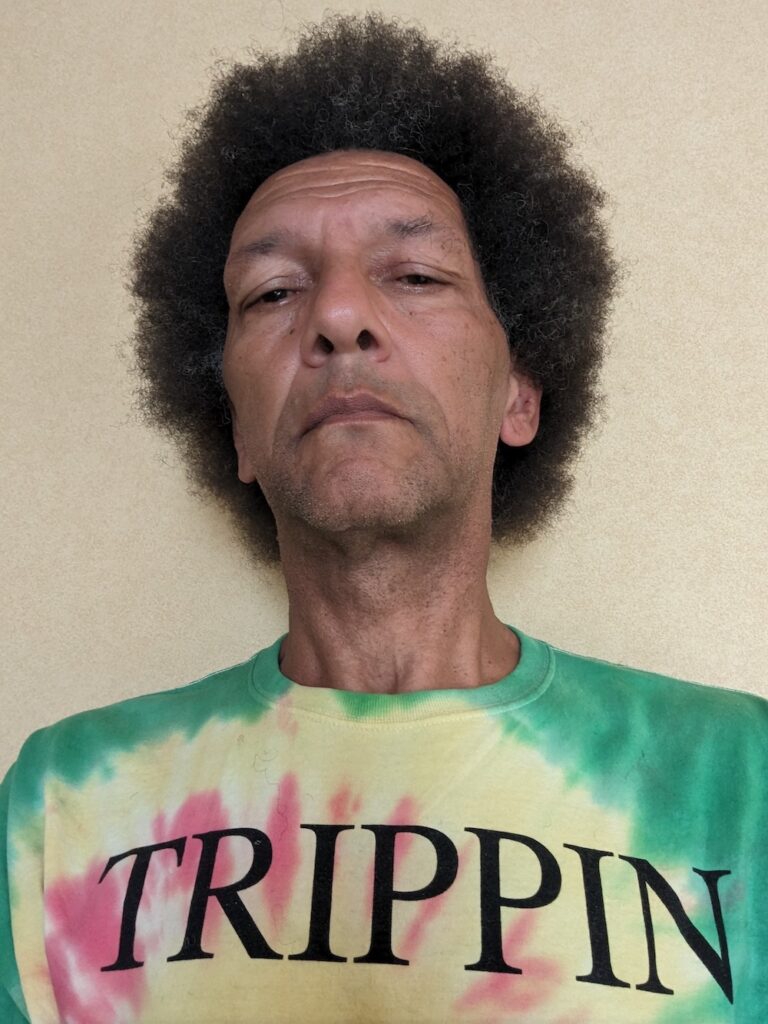

The photo that popped up

On the online front, social media and other searches turned up a dozen or so Miriam Katzs, but none age 85. Somewhat desperate, I tried a seemingly shady website for amateur sleuths looking for dirt. For $26 I could get a report on an 85-year-old Miriam Katz. As soon as they processed my credit card, up popped the report with a photo: She looked like me in a wig. My husband Tony walked in just as I opened the report and he said, “Oh my God, that’s your mother!” But was she still alive?

There were seven phone numbers that may have been associated with her. Two were cell phones. I texted both.

My heart was racing and couldn’t believe this was happening. I can only imagine how stunned she was. Much more texting ensued, exchanging photos, asking and answering questions. We set up and had a video chat. She has always been known as Mimi. She was an undergrad at Boston University and went to Pittsburgh as the maid of honor for her college roommate’s wedding in January of 1960. On the evening of January 13, at the wedding, she met Larry Bell, and after several cocktails, they “hooked up” as we might say today. Indeed, as we had guessed, she never told Larry she was pregnant. I was born exactly nine months later, on September 13. 1961.

Larry may have been the last man Mimi was with. She was attracted to women, and, in fact, never felt quite right as female herself. She felt more like a man but had no vocabulary to express these feelings. Today she describes herself as lesbian and non-binary.

She said she never had other children, but later I referred to my mysterious half-sister who ghosted me. Mimi was visibly uncomfortable and went on to reveal that yes, I have a half-sister, but she isn’t ready to talk about it.

We agreed I would travel to Brookline, MA on October 21,to meet in person and spend an afternoon together.

The big day came, and Mimi arranged for us to be hosted by Cheryl, a former lover and longtime friend with a home in Brookline. I didn’t know what to expect or how I would feel—would it all be too much? I was calm but trepidatious.

We embraced at the door and sat down in Cheryl’s living room to talk.

Ari and Mimi at their first meeting

I learned about her emotionally unavailable but highly intelligent parents. Her mom was a communist party member until the 1939 Hitler-Stalin pact and was a schoolteacher, and her father was a dentist. The only emotional warmth and connection she remembers was with her grandmother, who emigrated from Ukraine in 1904. Her grandmother lived in the same home with Mimi’s family and she often did her Russian Jewish cooking with Mimi at her side, much as my own mom did with me when I was young.

Mimi’s only sibling, a sister five years older, was sexually abusive toward Mimi during her childhood. She thinks this partially explains her difficulty feeling her own emotions throughout her lifetime. Eerily, I feel the same way, because my older adopted brother was also sexually and physically abusive toward me. I too struggle with feeling or connecting to my emotions. We both have difficulty recalling details as, apparently, we’ve both sealed ourselves off from the trauma.

As for my half sister born three years before me, this too was an exceedingly difficult episode that I will not detail here. Mimi had no agency and did as she was told by her family; she did not know this baby was placed through the Louise Wise agency until I told her.

When it came to the drunken night of her college roommate’s wedding in Pittsburgh three years later, when Mimi was age 23, her encounter with Larry, my birth father, was a positive experience, to the extent she remembers it. She has always thought she made the right decision giving me up for adoption, as she knew she was not equipped to raise a child properly.

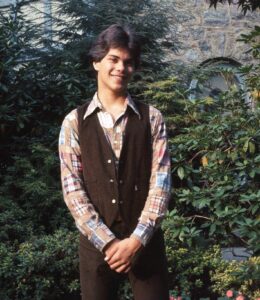

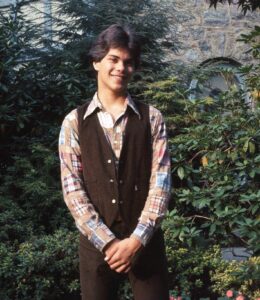

Young Larry

In the early 1970s Mimi founded the Northampton Common Womyn’s Collective with 10 lesbian friends. Many of these friends and former lovers are part of Mimi’s family today in the greater Boston area; they raised children together and now have many grandchildren, and Mimi is always part of every family celebration and milestone.

In the 70s, Mimi was drawn to meditation and various Hindu practices, and became attached to Andrew Cohen, a spiritual leader at the time. Mimi was his personal assistant. She travelled the world with him for many years, until financial and psychological abuse allegations surfaced, and Mimi eventually left his cult in 2003. A documentary, How I Created a Cult, was made for television in 2016, and Mimi is featured in it. It was surreal watching it after having just discovered and met her.

After our visit, I feel certain we will remain in contact and hopefully visit each other from time to time. I continue to enjoy the relationship with my new family, and I feel a new sense of completeness, now knowing so much of my “self” is informed by my genetics. It’s such an odd but pleasant feeling—being connected to my birth family now, after 62 years; I feel like these are my people.

My cancer remains stable, and I intend to make whatever time I have left rich with new experiences and meaningful human connections.

December 2023

Ari at 16

Young Mimi

Mimi’s mother, Mimi, Mimi’s grandmother

Ari Spectorman, age 62, recently sold his financial advisory firm and lives in New Hope, PA with his husband of 45 years. Follow him on Facebook, Threads, and Instagram.

Severance Magazine is not monetized—no subscriptions, no ads, no donations—therefore, all content is generously shared by the writers. If you have the resources and would like to help support the work, you can tip the writer. Venmo: @Ari-Spectorman

I, Louella Dalpymple, am an avid learner, so when I became an adoptive mom, I immediately labored to read a wide array of adoption agency websites so I’d be fully armed to endear myself to my children for all eternity. Now that my adoptees are adults, I feel obligated to share “lessons learned” with the rest of you.

I, Louella Dalpymple, am an avid learner, so when I became an adoptive mom, I immediately labored to read a wide array of adoption agency websites so I’d be fully armed to endear myself to my children for all eternity. Now that my adoptees are adults, I feel obligated to share “lessons learned” with the rest of you.