Searching for Mom, an award-winning memoir by Sara Easterly, pulls back the veil on adoption, revealing its harsher side—the primal wound that leaves a child desperate to feel worthy, to belong, to be good enough. Easterly was adopted at two days old, born to an adolescent girl coerced to relinquish her in a “grey-market” adoption. She had difficulty attaching to her adoptive mother and struggled with feelings of abandonment by her birthmother, which spurred an impossible quest for perfection, a crisis of faith and trust, and a battle with overwhelming emotions. She felt broken and cast off, unwanted. To protect her adoptive mother’s feelings, she suppressed her deep longing for and curiosity about her birthmother, putting her own needs and desires last to keep a peace, until finally, when she was nearly 40, she admitted her desire to search. Her adoptive mother reacted with a cocktail of emotions including fear, anger, and defensiveness. And then everything changed, when she revealed that in fact Sara had been wanted by her birth mother, causing Sara to reevaluate everything she’d come to believe. In Searching for Mom, Easterly traces her search for, and reunion with, her birthmother, the strain it placed on her relationship with her adoptive mother, and the complicated bond she shared with both women. More than a search tale, it’s a story about love, faith, and spiritual transformation. Here, the author shares an excerpt from her compelling memoir—its first chapter.

—BKJ

Taking Flight

We who are strong have an obligation to bear with the failings of the weak, and not to please ourselves.

—Romans 15:1 (ESV)

Monday morning. I’d flown home to Seattle, back from Denver long enough to toss dirty clothes out of their suitcases and start a load of laundry. While my two daughters reacquainted with their dolls and Magna-Tiles, I recalled my mom’s response when I’d told her that I planned to return to Denver for another visit the following week.

“Oh. I’m not sure I’ll still be here then, Sara.” Mom started to say goodbye.

I cut her off.

“No. I’ll see you again.” I smiled, trying to pretend this was any other farewell. Trying to convince her—convince myself—that this wasn’t really The End. There was no way Mom was dying. I’d been fabricating this kind of confidence about her life for the last five years.

But goodbye was in Mom’s eyes. Goodbye was in her embrace, weak as it was, even though I’d grown accustomed to “air hugs”—lest I spread germs to her highly susceptible lungs and body.

Suddenly, I felt sure of nothing. I faked my way back to life-as-usual on the plane ride home, barely able to process anything my children were saying. I was Mama-on-Autopilot, dragging carseats off the plane, lugging weary bodies into the car and then inside the house, washing airplane crud off tiny hands. Not that any of this was unusual. Numbed-out mom dutifully attending to the needs of small people while furtively fixating on a swirling emotional storm was one of my specialties.

I needed to talk to someone so I called a close friend. Heather had been through this herself, when her mother died a few summers earlier.

“You’re back in Seattle?” she asked skeptically, confirming my unease.

“Yes, but I’ll go back to Denver again next week,” I said. “I told my mom I’m going to go back again next Monday.”

After an awkward pause, Heather said, “I hesitate to tell you this, but the end can go pretty fast.”

“Faster than a week?”

“I’m sure it’s different for everyone,” she said. “I just know it went really fast for my mom. I wasn’t prepared for that.”

Unsettled, I called my sister for reassurance.

“I don’t know how to explain it, but there’s been a change since you left,” Amy said.

Even though we’d been home for less than an hour, I moved full throttle, rebooking a flight back to Denver that would leave in two hours. After dropping Violet and Olive off at a friend’s house, I sped my way through childcare and scheduling plans while en route to the airport—calling my in-laws, the preschool teacher, babysitters, and my closest friends and neighbors.

For a moment, I paused from the grim matter at hand to applaud myself. As a new parent I’d learned about the importance of a support village—something often lacking in this isolating age without live-in grandparents or “aunties” next door, and thanks to a fleeing-from-church culture. Mindful of this, and in lieu of in-city grandparents and church-based community, I’d deliberately worked to surround my family with our own “village.” Look at those efforts pay off! I told myself.

All the week’s plans came together as I rounded my way into the parking garage at SeaTac airport. My husband Jeff, who’d been on a business trip, would land in Seattle within thirty minutes of my flight’s departure out of Seattle. That left just the right amount of overlap for me to hand him the car keys, tell him he’d find the car in row 5J of the parking garage, text him the week’s schedule for the kids, and kiss his stunned face on the cheek.

As an event planner by trade, I’d always been a master of logistics. But I usually spent months working on each event. This rushed effort surpassed anything I’d attempted before. Did I have help on my side? I wondered, and then caught a flit of an answer: Maybe this is the kindness God doles out when your mom is dying. In any case, the fact that everything lined up so effortlessly and would be so gentle on my daughters, made me think that I was flying in the right direction. I just hoped I’d get there in time.

More importantly, I hoped to be up for the challenge. Mom had been preparing for her death for the last four months, but that didn’t mean I had.

Sure, I’d read Final Gifts: Understanding the Special Awareness, Needs, and Communications of the Dying by Maggie Callanan and Patricia Kelley. I’d even bought copies for my dad, sister, aunt, and grandma. I’d read about a dying mother who kept appealing to her family with travel metaphors, but whose family didn’t grasp that her last request wasn’t literal, which created a lot of unnecessary anguish for everyone during her final days.1 As a writer and reader, looking for meaning was right in my wheelhouse. I figured I’d be equipped to decipher any metaphors Mom might employ.

I’d also found out that dying people often converse with someone significant from their past who has already died, and how upsetting it can be for them if they aren’t believed. According to Callanan and Kelley, family members are the most qualified to figure out any of the hidden messages that could come from one of these conversations.2

When I was in my twenties, my deceased grandfather visited me during a dream while I slept on the pull-out sofa at my grandma’s place. It was a comforting dream, but the intensity of it began to pull me from sleep. My adored Papa was right there, I knew, and I fervently wanted to see him again. As my eyes slowly opened, I watched Papa’s translucent shape, lying right next to mine, evaporate. The mystical moment, too, dissipated. For the next two days I pondered talking to Mom about it. I wanted her to help me understand this encounter I’d had with her father, but she was a self-described “fundamentalist Christian,” and I figured she’d judge my spiritual experience as “New Age nonsense.” When I finally worked up my courage and recounted the story, though, Mom urged me to call Grandma.

“She’s been waiting for a sign from Papa,” she said, “She’ll want to know he’s at peace.”

Mom had helped me decipher Papa’s hidden message, and I, in turn, planned to help her. Maybe there’s more mystery around death and dying than we realize. I planned to be open to it, anyway. As Callanan and Kelley had said, “We can best respond to people who experience the presence of someone not alive by expecting it to happen.”3

Expectant or not, this was mostly practical book learning—savory knowledge that fed my brain and my propensity as an adoptee to believe in far-fetched stories. My emaciated heart, meanwhile, beat with a hankering for more.

Because my heart knew that I’d been afraid to face the reality of Mom’s declining health. I’d been too scared to speak important things that needed saying. I passed over vulnerable opportunities with jokes, denial, indifference, feigned confidence, forced control. I’d locked my feelings in a thick protective casing so I wouldn’t have to deal with whatever I was supposed to feel when I thought about the rest of my life without my mom—while wrestling with memories of our last two tumultuous years.

Deep down, did I ever even accept her as my mother? I would miss her for sure. Perhaps more for my daughters, only four and five, who wouldn’t get a chance to truly know her. But would it profoundly affect me when she was gone?

I felt so detached as I stared at the grey clouds outside the airplane window. But I’d vowed to give Mom myfinal gift: the peaceful death she deserved, the death a Good Adoptee4 owed her, the death I felt I needed to give her to prove my appreciation and loyalty.

I reached under the seat for my laptop and began compiling family photos for her memorial slideshow. I planned to leverage my event-planning skills to pull together the funeral she never would have dared to dream up.

Turbulence began to agitate the plane—the tell-tale sign that the Rocky Mountains were behind us as we approached Denver. I gripped the arm rests of my seat as the plane jerked in the sky.

Pushing away my feelings to give Mom what she needed was my training ground for becoming a parent. Ignoring my needs helped me get the job done: Making dinner when I’d rather be lounging on the couch devouring a good book … setting aside my own upsets or fears in order to soothe equally intense ones for my girls … hiding my true feelings in the face of hopes and disappointments. This all served me as a mother, didn’t it?

When I dared to look at the truth, I knew it served me as a daughter, too. It’s how I’d learned to stay safe, keep Mom close. Dutifully choosing her needs over mine ensured that she’d never leave me. Surely that’s where everything went so wrong, where I’d messed it all up, with my first mother.

Only Mom was about to leave me, too.

Images of being severed from her approached as fast as the plane slammed onto the tarmac. I thought about the pictures I’d just looked at—Mom’s glowing face, delighting in me, proud of me. Would I ever exude that much love for my daughters, the way Mom overflowed with it for us? Could I be as present as she always seemed to be?

Remember her manipulation and lies, though, I reminded myself. Her jealousy. Her mean streak. The last two years of mother-daughter turmoil because I broke the silence, stopped pretending … Those all told a different story.

A story I didn’t want to end this way.

A story I didn’t want to end at all.

I didn’t want Mom to die, and I definitely didn’t want our “us” to conclude before I could find the words my heart longed to say. I wanted to grow, become the person I yearned to be. A daughter—and a mother—who didn’t act out of obligation, a girl whose heart wasn’t unflappable, a human who dared to feel.

If only it were that easy.

© 2019 by Sara Easterly. All rights reserved.Sara Easterly is an adoptee and award-winning author of books and essays. Her memoir, Searching for Mom, won a Gold Medal in the Illumination Book Awards, among many other honors. Her essays and articles have been published by Psychology Today, Dear Adoption, Red Letter Christians, Feminine Collective, Her View From Home, Godspace, and others. Find her online at saraeasterly.com, on Facebook, on Instagram @saraeasterlyauthor, and on Twitter @saraeasterly.

Read her essay on Severance here.

If you’ve made a shocking family discovery, it likely threw you off balance, maybe even knocked you down. You may have been—may still be—bewildered, angry, hurt, confused, anxious, depressed, or ashamed. You may have experienced all of these emotions and others in succession, all at once, or in an unpredictable pattern. You may feel overwhelmed and unable to make sense of all the feelings and at a loss about how to communicate your thoughts. That’s why licensed therapist Eve Sturges created Who Even Am I Anymore: A Process Journal for the Adoptee, Late Discovery Adoptee, Donor Conceived, NPE, and MPE Community. Host of the popular podcast Everything’s Relative with Eve Sturges and an NPE (not parent expected) herself, she’s deeply familiar with the many ways the revelation of family secrets can sideline a person. It’s not a substitute for therapy, nor was it intended to be, but this first-of-its-kind journal is just the tool many need to help them on this unexpected journey; and for those who are in therapy, it can play a role, helping them think about their reactions and improving their ability to articulate their feelings. Sturges doesn’t provide answers. Instead, she offers prompts to stimulate your thoughts and kickstart self-expression. She asks questions and provides a safe space in which you can explore the answers, either privately, within a group, or with a therapist. Deceptively simple, it’s a crucial resource that’s certain to make a difference for thousands of NPEs and MPEs.BKJ

If you’ve made a shocking family discovery, it likely threw you off balance, maybe even knocked you down. You may have been—may still be—bewildered, angry, hurt, confused, anxious, depressed, or ashamed. You may have experienced all of these emotions and others in succession, all at once, or in an unpredictable pattern. You may feel overwhelmed and unable to make sense of all the feelings and at a loss about how to communicate your thoughts. That’s why licensed therapist Eve Sturges created Who Even Am I Anymore: A Process Journal for the Adoptee, Late Discovery Adoptee, Donor Conceived, NPE, and MPE Community. Host of the popular podcast Everything’s Relative with Eve Sturges and an NPE (not parent expected) herself, she’s deeply familiar with the many ways the revelation of family secrets can sideline a person. It’s not a substitute for therapy, nor was it intended to be, but this first-of-its-kind journal is just the tool many need to help them on this unexpected journey; and for those who are in therapy, it can play a role, helping them think about their reactions and improving their ability to articulate their feelings. Sturges doesn’t provide answers. Instead, she offers prompts to stimulate your thoughts and kickstart self-expression. She asks questions and provides a safe space in which you can explore the answers, either privately, within a group, or with a therapist. Deceptively simple, it’s a crucial resource that’s certain to make a difference for thousands of NPEs and MPEs.BKJ Born a member of the Confederated Salish Kootenai Tribes on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana, Vicki Charmain Rowan was adopted at two by a white couple who renamed her Susan. Already, at two, it was as if she were a child divided.

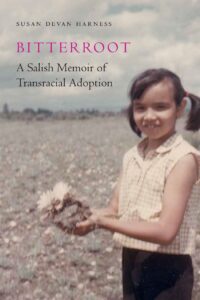

Born a member of the Confederated Salish Kootenai Tribes on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana, Vicki Charmain Rowan was adopted at two by a white couple who renamed her Susan. Already, at two, it was as if she were a child divided.

Rebecca Carroll, author, cultural critic, and podcast host, was adopted at birth by a white couple and raised in a predominantly white community in rural New Hampshire, where, as the only black resident, she’d see no one who looked like her until she was six years old. Growing up among her white relatives and white townspeople, she had no touchstone for what it meant to be black, no mirror of her own blackness to reflect and illuminate who she really was. And worse, no one cared. Her only point of reference as a child was the character Easy Reader from The Electric Company, whom she fantasized was her father. When she first encountered a black person in real life—her ballet teacher, Mrs. Rowland—she wondered, “Did she know Easy Reader from The Electric Company? Did she go home at night to live inside the TV with him and the words and letters he carried around with him in the pockets of his jacket?” As she grew older, Carroll was aware of being seen by this teacher in a way her parents did not, yet she was also aware of the differences. “I felt small pangs of fragile awareness regarding who I might be, what my skin color might mean. There were days when I wanted to be, or believed I was, black just like Mrs. Rowland, but it also seemed as though I would have to give something up in order for that to remain true.” She was increasingly aware that unlike her teacher, she moved through the world with the “benefits afforded by white stewardship.”

Rebecca Carroll, author, cultural critic, and podcast host, was adopted at birth by a white couple and raised in a predominantly white community in rural New Hampshire, where, as the only black resident, she’d see no one who looked like her until she was six years old. Growing up among her white relatives and white townspeople, she had no touchstone for what it meant to be black, no mirror of her own blackness to reflect and illuminate who she really was. And worse, no one cared. Her only point of reference as a child was the character Easy Reader from The Electric Company, whom she fantasized was her father. When she first encountered a black person in real life—her ballet teacher, Mrs. Rowland—she wondered, “Did she know Easy Reader from The Electric Company? Did she go home at night to live inside the TV with him and the words and letters he carried around with him in the pockets of his jacket?” As she grew older, Carroll was aware of being seen by this teacher in a way her parents did not, yet she was also aware of the differences. “I felt small pangs of fragile awareness regarding who I might be, what my skin color might mean. There were days when I wanted to be, or believed I was, black just like Mrs. Rowland, but it also seemed as though I would have to give something up in order for that to remain true.” She was increasingly aware that unlike her teacher, she moved through the world with the “benefits afforded by white stewardship.” Why highlight a book about the craft of writing in a magazine for adoptees, donor conceived people, and others who’ve experienced misattributed parentage? What does it have to do with you?

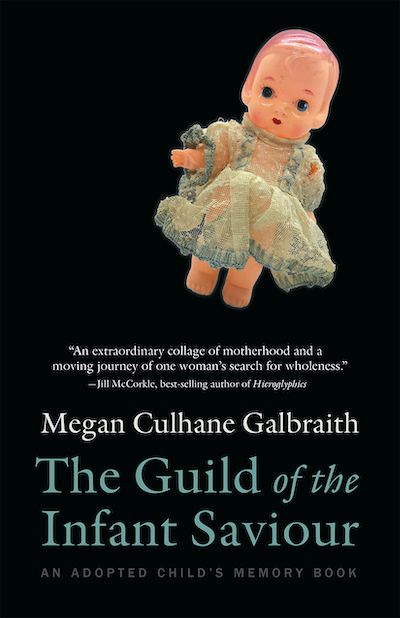

Why highlight a book about the craft of writing in a magazine for adoptees, donor conceived people, and others who’ve experienced misattributed parentage? What does it have to do with you? It’s not hyperbole to say I’ve never seen a book quite like Megan Culhane Galbraith’s extraordinary hybrid work of creative nonfiction, The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book. Experimental in form and structure, it’s memoir, but at the same time a striking visual art project, an intellectual inquiry into the nature of memory, and a frightful window on the failures and brutalities of the American system of adoption.

It’s not hyperbole to say I’ve never seen a book quite like Megan Culhane Galbraith’s extraordinary hybrid work of creative nonfiction, The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book. Experimental in form and structure, it’s memoir, but at the same time a striking visual art project, an intellectual inquiry into the nature of memory, and a frightful window on the failures and brutalities of the American system of adoption.