Meeting My Daughter

By Tom Staszewski

January 15, 2022 marked the second anniversary of the enactment of New York State’s Clean Bill of Adoptee Rights law allowing adoptees over the age of 18 unrestricted access to their sealed birth certificates. With that legislation, New York State became the tenth state in the US to allow open birth records.

When I first read about this new “open records adoption law,” little did I know it would have a direct impact on me. As I read the details about the legislation, I remember thinking it was rightfully so, that adult adoptees should have the same equal access to their birth records as non-adoptees. There should be no difference between treating one class of person differently than another based solely and entirely on the circumstances and events of their birth.

I certainly realize adoption is a complicated issue. Whether or not to place a child up for adoption is a difficult decision and a situation that often has no right or wrong answers. But it’s a topic that has been on my mind ever since 1970—the year my daughter, Victoria, was born.

Ever since she was adopted, and throughout all of those years since my high school days, I thought about her regularly and hoped and prayed she was alive and well. I always wondered if she was having a good life.

New York State open records law enabled Victoria to obtain her original birth certificate (OBC) and to then find her birth mother, who then subsequently gave her information that led her to find me as well. May 15, 2020 was a very happy day for me. I was surprised to find in my mailbox a letter postmarked from New York City. “Hello, I’m your daughter,” it said. As I read her letter, I was elated to learn that she was well, healthy, accomplished, successful and physically fit. She’d completed nine marathons, including the prestigious NYC Marathon. She also works out at a boxing gym with full contact sparring. And she’s earned a master’s degree. After I read all of the details about her life, I breathed a huge sigh of relief. It was a blessing that she was able to find me and for me to finally know that she’d had a good life.

I’ve long believed that a college degree is a passport to a better life and opens more doors of opportunity throughout one’s life, so I was extremely pleased to learn about Victoria’s level of higher education.

Unlike some adoption searches that lead to rejection, I was ecstatic to be identified, located and contacted. I fully recognize and acknowledge the role of her adoptive parents, now deceased and I’m thankful for their outstanding and exemplary job in raising her. Through their hard work, she developed into a very accomplished adult and a productive contributing member of society.

On the other hand, I readily admit, that as a foolish, silly, goofy, immature kid back in 1970, there was nothing I could have provided her. I had no job skills, no talents, no credentials. An awkward teenager, I didn’t realize the importance of personal responsibility and accountability. In addition to being an irresponsible kid, I lacked empathy, social gifts, and concern for others. I finally learned, acquired, and implemented those important empath type skills, traits, characteristics, and effective social skills when I was in my mid-20s. Therefore, I am so glad and thankful that her adoptive parents had the resources to provide a solid and stable life for her.

I was also very glad to see the letter’s origin was from Brooklyn, NY. I love NYC having visited there more than 25 times. It’s a much better location to visit rather than, say, Wyoming (with no disrespect meant toward that fine state). It’s just that I’ve always loved and am very comfortable being in large densely populated major urban cities. And my wife, Linda, and I have a longstanding tradition of going to Manhattan during the December holiday season. So I began to think of now being able to visit Victoria in NYC in just seven months. But of course, in December 2020 we had to cast aside our tradition because of the COVID shutdown.

After I read all of the details about her life and breathed a huge sigh of relief, I couldn’t help but also notice that her letter was well crafted. She expressed a strong command of the English language and had an exceptional vocabulary. Her writing was clear, concise, and coherent.

Please don’t misinterpret my positive critique of my own daughter’s first correspondence to me. As a career academician, I’ve read and graded thousands of graduate-level term papers, research papers, portfolios, and projects. It was only natural for me to notice her proficiency and the important skills displayed in Victoria’s first letter to me.

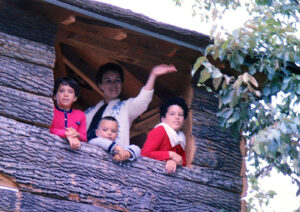

I responded by telephone, and since then we’ve communicated by, phone, and e-mail, and we’ve exchanged dozens of photographs from various stages of our lives. But more important, we finally met in Midtown Manhattan on December 4th, 2021—a very happy, momentous, and memorable day indeed!

Throughout my academic career, I’ve always been fascinated by the ongoing debate about heredity vs environment, nature or nurture, and genetics in general. As we got to know each other, I was intrigued to find that we have many similarities and have had mutual experiences. We both were raised as Catholics, had paper routes, played the accordion, worked at McDonalds’s as young kids, and while in high school worked in delis. We’re involved in local politics and registered to vote with the same political party. In school, math was (and is) a mutual weakness.

Ever since I was fifteen years old, I’ve had a passion for being physically fit, spending long hours each day exercising and working out in health clubs and gyms. So I was very impressed when I read that Victoria was a long-distance runner and completed nine marathons. The grit, determination, mental-toughness, persistence, and hard work she exhibits as a competitive long-distance runner are qualities and traits I’ve always admired and respected in others. I was also impressed that she practiced boxing and full contact ring sparring. So maintaining health through physical fitness is yet another interest we share. In my estimation, our many similarities lend credence to the premise that human behavior, preferences, and tendencies are genetically determined.

According to the Adoptee Rights Law Center, Minn. MN (2022), many non-adopted people do not know that an original birth certificate (OBC) is the initial birth certificate created shortly after a person’s birth. For most people, it’s their only birth certificate. For persons born and adopted in the US, a new or “amended” birth certificate replaces the OBC once the adoption is final. I strongly believe other states should follow New York’s lead and pass legislation that would equalize the fundamental right of adults to access their own pre-adoption birth certificates. To deny that access is unfair and unwarranted. Adult-aged adoptees should have the same right as non-adoptees to obtain their own birth records. I applaud all of the New York state elected officials who rectified the unfair treatment of adoptees. Thanks to them, it’s an inequality that’s been righted.

Other state government entities should realize that the rights of adult adoptees to be treated the same is mainly an equality issue. The core issue behind open OBC legislation is not just about searches and reunions; it’s about the removal of a discriminatory barrier to a legal document. I believe that continuing to treat one class of persons differently than another based solely on the circumstances of their birth is not right and must be corrected…the sooner the better.

I realize the controversy associated with this issue and know that not every search results in such a positive outcome as it did in my situation. But I firmly believe the benefits outweigh the risks. Without that access, adopted people are unfairly left wondering about their identities and origins. It leaves them without valuable and factual information about their very existence. The law undoes decades of discrimination. That alone is justification for such legislation to occur.

I understand there may be privacy concerns after decades of secrecy. In previous decades, adoption records were routinely sealed as there was a prevalent societal norm of shame and scorn directed toward individuals who had teenage pregnancies. And in past generations, the commonly used negative and condescending label of illegitimate birth was the norm.

But, thankfully, societal attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions about the adoption process have shifted. Judgmental negative viewpoints are changing and the stigma is lessening.

Victoria is truly wonderful! She’s remarkable, accomplished, talented and beautiful. I’m so glad that I had an opportunity to finally be with her and hug her. I can’t wait to walk back md forth across the Brooklyn Bridge with my new daughter on my next visit to New York.Tom Staszewski, EdD, lives in Erie, PA with his wife, Linda. He retired in 2014 following a 35-year career in higher education administration. His doctorate in higher-education administration is from the University of Pittsburgh. He is the author of Total Teaching: Your Passion Makes It Happen, published by Rowman & Littlefield.” Contact him at tomstasz@neo.rr.com.

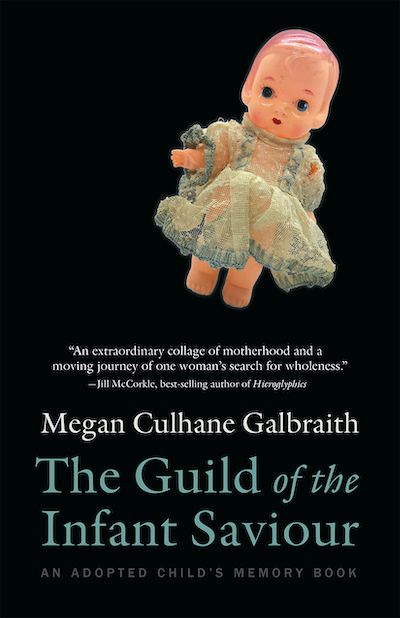

It’s not hyperbole to say I’ve never seen a book quite like Megan Culhane Galbraith’s extraordinary hybrid work of creative nonfiction, The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book. Experimental in form and structure, it’s memoir, but at the same time a striking visual art project, an intellectual inquiry into the nature of memory, and a frightful window on the failures and brutalities of the American system of adoption.

It’s not hyperbole to say I’ve never seen a book quite like Megan Culhane Galbraith’s extraordinary hybrid work of creative nonfiction, The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book. Experimental in form and structure, it’s memoir, but at the same time a striking visual art project, an intellectual inquiry into the nature of memory, and a frightful window on the failures and brutalities of the American system of adoption. Tell me a little bit about your background, how you came to be interested in creating DNAngels, and how you educated yourself about genetic genealogy?

Tell me a little bit about your background, how you came to be interested in creating DNAngels, and how you educated yourself about genetic genealogy?