By A.D. HerzelThe return flight was most memorable. A six-month-old boy slept in my lap for 18 hours, never crying once. He was not my baby and legally no longer belonged to the woman who gave birth to him. On many papers signed by governments and agencies on opposite sides of the world, he belonged to a family in the United States. I was 19, and my thoughts and memories reeled back and forth through time. I reflected upon the experiences and challenges I had encountered as an Asian adoptee in America, and I wondered about the known and unknown possibilities his future would hold. As I thought about his journey to the other side of the world, I silently cried. Did anyone notice? No one said a word. My tears fell on and off through the course of the long night. We were flying together in limbo, he and I leaving one home on the way to another, though I felt neither place was truly ours to claim. Was this only my story? Would it be his too?

In the summer of 1987, after I completed my first year of college, my adoptive parents generously sent me on the Holt Motherland tour. Holt international was an Evangelical Christian adoption agency founded by Harry Holt and his wife, Bertha, in 1953. Harry Holt is credited with creating the logistic and legal pathway for the intercountry adoption of Korean children to families in the United States. The Motherland tour was an effort by the Holt organization to create an opportunity for adult Korean adoptees to learn about their Korean heritage and visit their “homeland.”

I did not ask to go on the tour, but when it was offered, I readily accepted. Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, I didn’t have much access to Korean culture. My parents were not the kind who celebrated or shared the beauty and culture of the country I and my two adopted siblings had come from. I recall meeting Bertha Holt on two occasions at large gatherings when I was very young. The evangelical church community my adoptive parents belonged to recruited new members throughout the suburbs of Long Island, New York. The church members adopted roughly 100 Korean children. I have a picture in my mind of us all posed in a hall with Bertha wearing a hanbok. Somewhere on Long Island, in a box of my now-deceased parents’ photos, it may be hidden.

Unlike most Korean adoptees dispersed into the white American population, I was raised among many other Korean adoptees and their families. When my parents’ church devolved into a conservative, Sephardic, Kabbalistic, messianic cult, I was in first grade. I was told we do not pray to Jesus anymore. Two of my brothers and I were put in its private religious school until sixth grade, where half of the children in my class were Korean adoptees.

Yet we never talked about being adopted. My best friend was a Korean adoptee, as was her sister. My adopted siblings and I talked quietly, privately, about many things, but never about our lives before adoption or our families on the other side of the world. We, according to my adoptive mother, were God’s will in her life, her mission. Thus, I was named Amy Doreen—beloved “gift of God.” Amy is a common name among Korean adoptees. When I was a child, I imagined it made me special. As a teenager, I held on to the name of “love,” hoping if I embodied it, it would come to me.

As I grew up, I came to find the name silly and ill-fitting. Amys were pretty, sweet, and bubbly. Cherished, they were something that was not me. Inside, and occasionally outside, I was mean, cutting with words, hungry, lonely, awkward, uncomfortable in my skin, angry, and always afraid. I cursed myself, as I was cursed at, and felt cursed. Being “God’s gift” was always a chain.

In a recent interview with an adoptee, she reminded me of my past self. I had forgotten the feeling of my anger, my self-hate. Though I spent my elementary school years in a religious bubble where I did not think about my race, when I was in my home, my neighborhood, and when I finally went to public school in seventh grade, I was harassed, afraid, and I hated being Asian. I cringed at the sight of another Asian in public or on tv. I was ashamed of being part of the denigrated class. I was taught at home that Asians were stupid and ugly and weak. Was I made fun of? Of course, this was the 70s.

After learning the breakdown of my DNA, I was reminded of having been taunted with “Chinese, Japanese, dirty knees, look at these!” I used to say, “I am Korean, stupid,” with fury and fear bubbling inside. The kids never knew what or where Korea was. But now I know. I am Chinese and Japanese and Korean. I knew it never really mattered. The truth was always clear. I was more interested in being invisible or at least visible on my own terms. It would take me decades before I even knew what my own terms were. This was never possible within my adoptive family or within the upper-middle-class Long Island suburbs where I grew up. I escaped Long Island and my adoptive parents’ home at the end of college and returned only for major family events.

My Motherland Tour shifted many things. The American spell of my “minority self”—”ugly, powerless, and unworthy”—broke when I saw the beauty of the landscape and the masses of people and witnessed the culture. It was an awakening that some Korean adoptees have, but not all. The tour helped create a space for “Korean pride”—a long well-guarded taboo. It was also the first time I actually spoke about the nature of my adoptive family struggles with fellow adoptees. How many tears were shed? How many cheap Korean cigarettes were smoked at Il San Orphanage, sitting around Harry Holt’s gravestone? No one understood. Counselors might have been helpful. Alcohol, cigarettes, tears, and late-night confidences carried us through the two-week tour—“orphans” once more figuring things out on our own. Seven of us were close in age and created an odd “Breakfast Club.” It was a strange brief enlightenment and a respite for those of us not wanting to return to the families that sent us. We would all return to our respective states—Tennessee, Minnesota, Wisconsin, South Dakota, California, Kansas, New Jersey, and New York—after sorely straining the nerves of the late Dr. David Kim, the former director of Holt International Children’s services.

The most profound stop for me on our tour was Holt’s unwed mother’s home. I do not remember the inside or anything I saw. I only remember being doubled over outside the building bawling my eyes out, finally having a complete emotional breakdown. I do not have memories of any words from the moment. A geyser of sorrow had broken free and I no longer had the will to fight it. The unwed mother’s home was considered progress—something Holt International was proud of. Dr. Kim always told us his dream was that adoptees would end up running Holt. I wonder how he interpreted all the tears and wailing sobs elicited by these annual tours.

As our tour bus obliviously rode through the South Korean peninsula, the June 1987 Democratic uprising was occurring. The demonstrations led to a democratic election and other reforms as well as the Great Workers’ Struggle, which was marked by the largest and most effective union organizing and walkouts in South Korean history. One night, our bus was stuck in the demonstration traffic, and several people were sickened by the tear gas that floated through the windows. The political struggle for Korean democracy was not on the Holt Motherland Tour cultural menu, so context was never given.

At 19 and older, had we grown up on the peninsula with or without our unknown birth parents, we likely would have been part of, or greatly invested in, the outcomes of the crowds on the streets.

Instead, we were buying tourist trinkets in Itaewon. “Eol meyeyoh? How much?” and “Kamsa hamneda, thank you,” were the pillars of our Korean language acquisition. My American freedom had already been bought by the war, by my adoption. I had not grown enough to truly protest with my fellow Koreans. In Korea, I was an “orphan” in an American wrapper, envied and looked down upon. In America, I was an American in a Korean wrapper, a dirty import.

Time has passed. The first experiments have grown up. The adoptee outcomes from the first wave of Korean adoptees and my subsequent generation resulted from prescriptions of assimilation and religious charity. Though research is scant and belated, it showed what many of us have privately known. A study by the Evan B Donaldson institute I participated in, reported by the New York Times in 2009, showed that 78% of Korean adoptees identified as white or wanting to be white. It also documented that, “as adults, nearly 61 percent said they had traveled to Korea both to learn more about the culture and to find their birth parents.” This shows us; the majority of adoptees assimilate and displace their identity with that of their foreign families, and that their innate identity is still almost equally important. Intercountry adoption and many forms of adoption demand the “erasure” of a life and identity prior to placement in the foreign environment, but identity can only be controlled by external forces for so long.

Revolution and a way to culture, identity, and citizenship reclamation is still being paved by adoptees born after me. According to data culled from US State Department reports by William Robert Johnston and the Johnston archives, only 4,400 Korean children were adopted the US in the 1960s. During the 70s, 25,247 Korean children were recorded as adopted to the US, and during the 80s, the number rose to 46,254. A small fraction of these younger and older adoptees would move back to Korea, search for birth families, and demand accountability from adoption agencies, the government, and their birth families. With the rise of the Internet and DNA technology, these numbers appear to be increasing, though they have yet to be measured.

Unceasingly, these same demands have been and will be replayed by every adoptee who understands what it means to ask for their rights as defined by the UN Rights of the Child Agreement. (The United States is one of the few countries that has not ratified, and does not subscribe to, the Rights of the Child Agreement.) Thus, our work continues: supporting Korean adoptees, making community, creating birth search and reunion resources, and sharing our stories in writing and through the arts. Today, adoptees are fortunate to find a varied handful of Korean adoptee-centered organizations, podcasts, and magazines online among them: ICAV, IKAA, AKA, KAMRA325, GOA’L, Adoptee Hub, the Adapted Podcast, and The Universal Asian.

When my return flight landed at JFK airport with the other HOLT 1987 Motherland Tour members, I was brought to meet the family waiting for the baby I carried. My service as an escort paid for my plane trip back to the US. I do not remember the name they gave him. I recall the family—white, with perhaps two older daughters. I may have intentionally not wanted to remember them. I had not wanted to give him up. I had not wanted to give him to them. I gave him up knowing, whether they were kind or not, the road could be difficult. America was uniquely hard on Asian boys. He would have questions they could not answer, desires for self-knowledge they could not fulfill, and my heart was inadequate and broken. I was still inadequate and broken.

I hope he was fine, was loved, was fairly treated, found pride, self-acceptance, friends, and self-love. He should be 34 now and still on the journey that never ends, reconciling the before and after, the with and without. My best hope is that he was one of those adoptees who was able to be proud and have an easy knowledge of his Korean cultural heritage and identity. What I could not do for him then is what I do now—share as much as I can and show what I am able.

And to him I say, “If you are out there looking for a friend on the road or the mule that carried you to America, here I am.”

미안해 Biahnay

I am sorry.

A.D.A.D. Herzel was “found” in 1968 in Hari, Yeouju eup, South Korea, and brought to the U.S. in 1970. She is a Korean American adoptee, visual artist, writer, and educator who has exhibited work nationally for the past 20 years. Trained as a painter and printmaker at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, she also earned her M.Ed. in art education from the Tyler School of Art. Her current project, titled Seeds from the East: The Korean Adoptee Portrait Project, will be shown in multiple venues in 2022-2023. These exhibits are scheduled for the Philip Jaisohn Memorial House in Media, PA, and the Eleanor D. Wilson Museum at Hollins University in Roanoke, VA. She’s working with Adoptee Hub for an exhibit in Minnesota, and plans are in the works for shows in Oregon and, possibly, Boston. She is also a regular arts contributor to The Universal Asian, which describes itself as an open and safe online database platform in a magazine-style to provide inspiration to Asian adoptees (#importedAsians) and immigrated Asians (#hyphenatedAsians) around the world. Learn more about her work here. Find her on Instagram @pseudopompous.Severance is not monetized—no subscriptions, no ads, no donations—therefore, all content is generously shared by the writers. If you have the resources and would like to help support the work, you can tip the writer.

On Venmo: @pseudopompousBEFORE YOU GO…

Look on our home page for more articles and essays about NPEs, adoptees, and genetic genealogy.

- Please leave a comment below and share your thoughts.

- Let us know what you want to see in Severance. Send a message to bkjax@icloud.com.

- Tell us your stories. See guidelines.

- If you’re an NPE, adoptee, or donor conceived person; a sibling of someone in one of these groups; or a helping professional (for example, a therapist or genetic genealogist) you’re welcome to join our private Facebook group.

- Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @Severancemag.

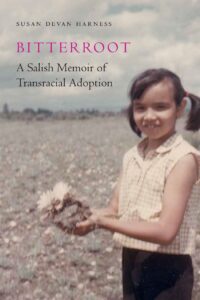

Born a member of the Confederated Salish Kootenai Tribes on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana, Vicki Charmain Rowan was adopted at two by a white couple who renamed her Susan. Already, at two, it was as if she were a child divided.

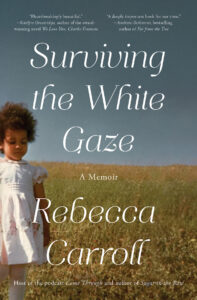

Born a member of the Confederated Salish Kootenai Tribes on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana, Vicki Charmain Rowan was adopted at two by a white couple who renamed her Susan. Already, at two, it was as if she were a child divided. Rebecca Carroll, author, cultural critic, and podcast host, was adopted at birth by a white couple and raised in a predominantly white community in rural New Hampshire, where, as the only black resident, she’d see no one who looked like her until she was six years old. Growing up among her white relatives and white townspeople, she had no touchstone for what it meant to be black, no mirror of her own blackness to reflect and illuminate who she really was. And worse, no one cared. Her only point of reference as a child was the character Easy Reader from The Electric Company, whom she fantasized was her father. When she first encountered a black person in real life—her ballet teacher, Mrs. Rowland—she wondered, “Did she know Easy Reader from The Electric Company? Did she go home at night to live inside the TV with him and the words and letters he carried around with him in the pockets of his jacket?” As she grew older, Carroll was aware of being seen by this teacher in a way her parents did not, yet she was also aware of the differences. “I felt small pangs of fragile awareness regarding who I might be, what my skin color might mean. There were days when I wanted to be, or believed I was, black just like Mrs. Rowland, but it also seemed as though I would have to give something up in order for that to remain true.” She was increasingly aware that unlike her teacher, she moved through the world with the “benefits afforded by white stewardship.”

Rebecca Carroll, author, cultural critic, and podcast host, was adopted at birth by a white couple and raised in a predominantly white community in rural New Hampshire, where, as the only black resident, she’d see no one who looked like her until she was six years old. Growing up among her white relatives and white townspeople, she had no touchstone for what it meant to be black, no mirror of her own blackness to reflect and illuminate who she really was. And worse, no one cared. Her only point of reference as a child was the character Easy Reader from The Electric Company, whom she fantasized was her father. When she first encountered a black person in real life—her ballet teacher, Mrs. Rowland—she wondered, “Did she know Easy Reader from The Electric Company? Did she go home at night to live inside the TV with him and the words and letters he carried around with him in the pockets of his jacket?” As she grew older, Carroll was aware of being seen by this teacher in a way her parents did not, yet she was also aware of the differences. “I felt small pangs of fragile awareness regarding who I might be, what my skin color might mean. There were days when I wanted to be, or believed I was, black just like Mrs. Rowland, but it also seemed as though I would have to give something up in order for that to remain true.” She was increasingly aware that unlike her teacher, she moved through the world with the “benefits afforded by white stewardship.”