If your DNA discoveries, searches, or genetic identity issues have caused you sorrow, the five stages of grief may not be a reliable guide to navigating bereavement.

By B.K. Jackson

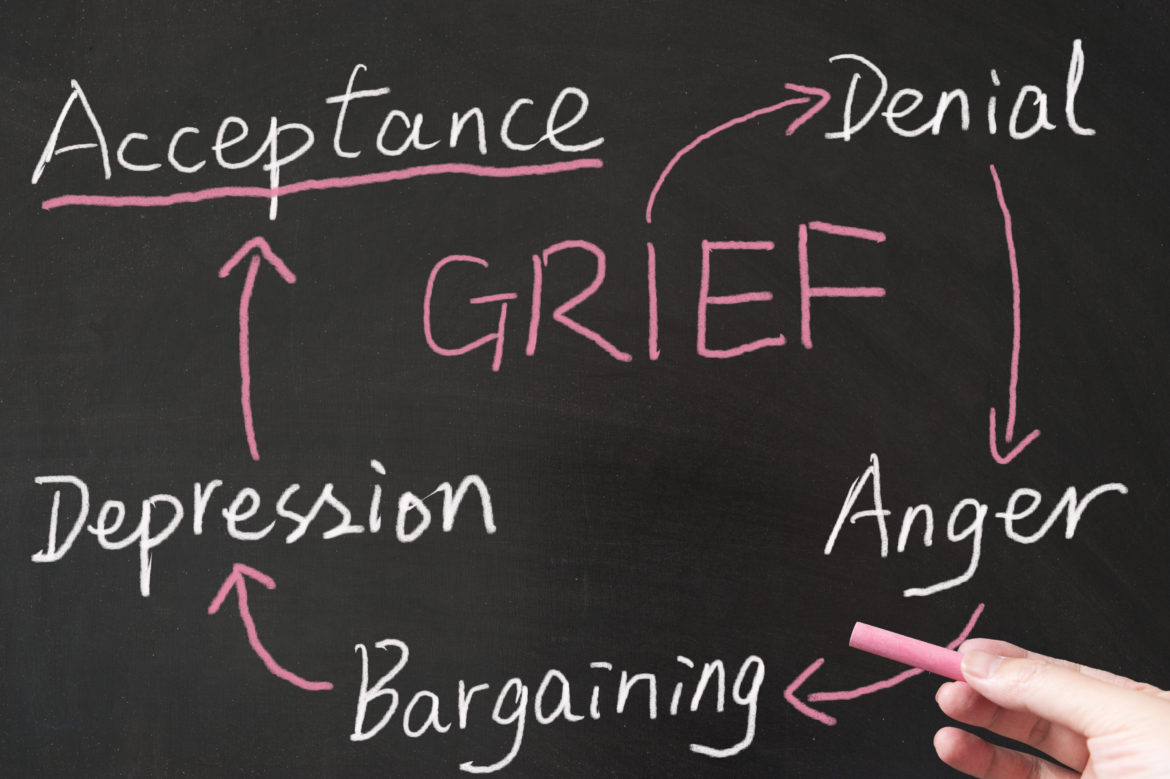

Everyone knows about the five stages of grief. And therein lies the problem. Introduced in 1969 by Elizabeth Kübler-Ross in her book “On Death and Dying” as a blueprint for the emotional responses experienced by people with terminal illness, the five stages of grief—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—have been applied, or, many argue, misapplied—to the experience of grief. The media touted the stages to such a degree that they became dogma, and now, decades later, they remain influential. They’re recommended by medical professionals to patients and by friend to friend, not only as guide to coping with the loss of a loved one but also as a balm for the emotions associated with any type of loss, whether a romantic breakup or a job termination. All this, despite the fact that there’s no scientific basis for the five stages, even for use with the terminally ill.

While the stages, arguably, may have limited usefulness as a tool in the hands of trained grief therapists and in end-of-life care, their value for helping individuals self-manage grief has been widely overstated and, according to some experts, misrepresented.

“So many people think grief is described by Kübler-Ross’s ideas about the five stages of grief,” says Kathleen R. Gilbert, PhD, professor emerita in the department of applied health science, Indiana University School of Public Health-Bloomington and an Association for Death Education and Counseling fellow in thanatology (FT). “But people don’t do those stages. The concept, she says, was devised by a chaplain who wanted to help people of his faith who were in the process of dying. It wasn’t based on research, she adds, only on his own belief system. Kübler-Ross appropriated the concept and applied it to people experiencing grief related to the loss of loved ones.”

The concept, Gilbert says, “feels real because it seems like such a nice progression. The problem is that we as a species don’t do progression well.” The stages don’t even work with the dying, she adds. “Nobody does it that way, but it feels good to think you’re not going to have to find your own way. But everyone has to find their own way because everyone grieves in their own unique manner.”

Mention the five stages to Pauline Boss, a family therapist, educator, and expert on loss—as we did in an interview—and she simply says, “Oh please!” She points out that “in Kübler-Ross’s last book, which unfortunately few people read before she died, she herself said they were meant for the person who was dying, not for the mourners. And she herself said grief is messy, not linear.”

David Kessler, who, having cowritten two books with Kübler-Ross—“Life Lessons: Two Experts on Death & Dying Teach Us About the Mysteries of Life & Living,” and “On Grief & Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief Through the Five Stages of Loss”—acknowledges that during the last 40 years the stages have been misunderstood. Still, in his forthcoming book, “Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief”—informed by the loss of his 21-year-old son—he continues to discuss grief in terms of the stages, even delineating a sixth stage—finding meaning. While he describes the five stages as “tools to help us frame and identify what we may be feeling,” he acknowledges, as Kübler-Ross did, that individuals don’t go through these stages in order. It’s a curious statement, though, since a stage, by definition, is a step in a process.

While Kessler agrees that “there’s not a typical response to loss as there is no typical loss,” he characterizes the stages as “responses to loss that many people have.” Yet even that’s a notion in dispute. Although Kessler says the stages were “never meant to help tuck messy emotions into neat packages,” many experts observe that they continue to be “prescribed” exactly for the purpose of compartmentalizing emotions into tidy categories, offering what may be an unreliable road map through grief—one that’s bound to make travelers who don’t experience the stages feel lost and confused. The problem, these experts suggest, is not only that the stages aren’t linear, but that they don’t truly represent the collective experience—because there really is no collective experience.

Numerous critics have noted conceptual weaknesses and over-simplification in the stage concept, some insisting it doesn’t stand up to scientific scrutiny. In 2003, Yale researchers looked at the grieving experience of 233 people, and although they found some aspects were as described by Kübler-Ross, others were not. They also found that the while Kübler-Ross described depression as the most intense of the reactions to grief, the grievers in their study pointed to yearning for their lost loved ones as the most powerful negative effect. And Columbia University psychologist and grief expert George Bonanno disputes the stage theory, suggesting instead that grief is experienced in waves, the severity of which diminishes over time. And in 2011, Ruth Davis Konigsberg argued against the usefulness of the stages in “The Truth About Grief: The Myth of its Five Stages and the New Science of Loss.”

In “Misguided Through the Stages of Grief,” Margaret Stroebe, Henk Schut, and Kathrin Boerner track the rise of Kübler-Ross’s stage theory and the subsequent variations offered by other scholars. In the article, they focus on “emergent lines of argument against stage theory, covering conceptual concerns, lack of empirical validity, its failure to assist in identifying those at risk or with complications, and the potentially negative consequences for bereaved persons themselves,” concluding that the stages miss the mark in each aspect. They argue not only that the steps have no utility, but also that they actually may be harmful to people who do not go through them. The stages, they believe, should be discarded and “relegated to the realms of history.”

If they have so little real value, how did these stages become so deeply accepted and ingrained as to become the gospel of grief? According to Boss, who’s working on a book about the myth of closure, “American society loved the five stages because they offer a way to get over it, to find closure, which is a very American idea,” she says. “You don’t hear people from Latin American, Mexico, or Asia ever talk about that. They don’t see it as necessary to have closure.” The idea that we need to get over loss and move on, Boss believes, is a uniquely North American idea.

So, what do you need to know about the five stages of grief? Forget about them. The steps are appealing because they offer comforting guideposts to the unknown and promise order and predictability. But grief is neither orderly nor predictable. Columbia University’s Center for Complicated Grief characterizes typical grief in simpler terms, dividing the experience into acute grief and integrated grief. The former is the intense experience of sorrow and yearning that overshadows an individual in the immediate aftermath of a loss. It may be accompanied by difficult emotions including guilt, anger, and anxiety. Integrated grief is the grief we live with and fold into our lives; it takes up less space but doesn’t disappear. Not a typical reaction to loss, complicated grief is when acute grief persists and continues to overshadow one’s life, interferes with normal life, and results in dysfunctional beliefs and behaviors.

If your feelings threaten to overwhelm you, it’s wise to seek help from a trained grief therapist, preferably one certified in thanatology (the scientific study of death and practices associated with it) and credentialed by the Association for Death Education and Counseling. A therapist can help even when grief isn’t all-consuming. If, however, you’re wading through so-called normal grief alone, remember that the use of words like “journey” and “path” don’t suggest there’s an endpoint. Grief is ongoing, meandering. It may be universal, but it’s not universally experienced. Your journey will be unique. There’s no timeline and you don’t need a map. You’ll find your own way, and it will take as long as it takes.

Whether it arises from the death of a loved one, the loss of a genetic identity, or rejection by birth family—grief is a wild, unpredictable tumbleweed and you’re along for the ride.