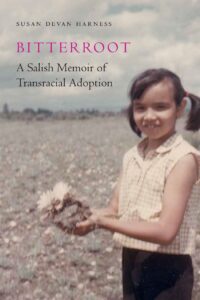

Born a member of the Confederated Salish Kootenai Tribes on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana, Vicki Charmain Rowan was adopted at two by a white couple who renamed her Susan. Already, at two, it was as if she were a child divided.

Born a member of the Confederated Salish Kootenai Tribes on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana, Vicki Charmain Rowan was adopted at two by a white couple who renamed her Susan. Already, at two, it was as if she were a child divided.

Susan Devan Harness has spent most of her life straddling two worlds, never having a secure footing in either, learning early that “It hurts to be an Indian” in the world in which she lives. Her extraordinary memoir, Bitterroot: A Salish Memoir of Transracial Adoption, is evidence that one can pluck a living thing from the soil in which it grew and plant it elsewhere, and though it may survive, surviving isn’t the same as thriving. Her account is a reckoning of a bitter isolation and a harsh record of a tenacious search for a sense of belonging. It’s a story streaked with a particular kind of loneliness, the kind that takes hold not in solitude but among people in whom the author can’t see herself reflected.

Raised by a mentally ill mother and an alcoholic father, Harness sees herself as different from those around her, and she’s acutely aware that she’s perceived as different, not only by the townspeople, but even by her father, whose lexicon is laced with ethnic slurs and who speaks derisively about Indians, describing them as gold diggers, deadbeats, “goddam-crazy-drunken-war-whoops.” She’s aware she’s not the cute little blond-haired blue-eyed girl her father says he always wanted. And at the same time that she feels hatred toward him, she’s aware of a self-loathing coiling inside herself.

She encounters few people who looked like her growing up, and she’s reminded at every turn that she doesn’t fit in. She lives in a kind of a gap between cultures where a question took root early: what did it mean to be Indian if she wasn’t raised in an Indian family? “The Indians don’t want me; the whites don’t accept me. They push me into each other’s court, always away from them. I am isolated; I am in-between,” she writes.

Harness fantasizes about finding her “real parents,” and yearns for them to feel real to her. “It is important they feel real because being Indian, living in this white family in this white town, and going to school with these white kids reminds me not only how different I am but how I will never be one of them.” So she dreams of the life that might be more authentic, “where I was ‘real’ instead of ‘adopted; a life where my skin color was the same as everyone else’s and I wouldn’t stand out, isolated; a life where ‘American Indian’ meant something more than ‘I don’t know.’”

When she’s a teenager, her father tells her her biological parents had been killed in a car accident, but years later, when she obtains a hard-won file of information about her adoption, she discovers there’d been no accident—that her mother, Victoria, is living only 30 miles from where she lives. In fits and starts, advances and retreats, Harness embarks on a quest to learn where she came from. She wants an origin story, a glimpse of her childhood, to find out what it means to be an indigenous person—the things no one in her family can tell her. She searches for her birth family and finds strangers. She tries to make meaning, but comes up hard against facts she can’t make sense of. “I don’t know why I was taken from a chaotic family filled with alcoholism and dismembered relationships and placed in a family with alcoholism and dismembered relationships,” she remembers. “My experience is that when I was removed from my blood family, then my birthrights, my membership in a family and a community, and the sense of who I was in the world were also removed from me.”

Although she develops a relationship with her mother and other members of her first family, there’s no place where she isn’t isolated, where she fully belongs, where she isn’t “other.” Still, she retains empathy for the family she can’t fully rejoin and is clear-eyed about the jagged complexity of reunions. “I had been flung to the waiting arms of a world who found Indians repulsive, with our lazy, drunk, promiscuous ways. The wounds I was left with still bled under the right conditions. And my being in her presence put me in emotional limbo. I had longed for this moment, fantasized about it when I was six, dreamed about it when I was fifteen. But my soul filled with dread as the reality check of who I really am seeped into the cracks of my fragmented identity.”

More than an account of her own story, Bitterroot is equally a biting indictment of the brutal assimilation policies of the U.S. Government and the historical injustices—the laws and treaties that dispossessed Native Americans in myriad ways. Harness comes to study anthropology and labors to bring about change in the child placement policy. She works with other transracial adoptees to shed light on their experiences of living in a white world as American Indians and explores their collective pain of not belonging.

Bitterroot is exquisitely written and deeply moving. It’s essential reading—achingly beautiful prose that will resonate with anyone who’s ever felt they weren’t enough, who’s had to fight for the story that should always have been theirs, who’s ever struggled to find a place to belong.

1 comment

Great article. Well written and informative. Thanks for sharing this story! The memoir should prove to be an interesting and worthwhile read. All the best to all involved!