An essay by Shannon Quist

In their defense, all the stories they heard about adoption were fairytales. All they knew was that their bodies could not make a baby together and there was a fairytale option in front of them, a socially acceptable alternative. Adopt a baby. And so, armed with the holy love of God and the righteousness of white privilege, they bought into a story that began with a happily ever after and cost them a pretty penny. Later, they would complain that they didn’t get the benefits of a tax break when adoption tax breaks became a thing. They paid for a human. They invested in a family experience. But investments like this don’t always go as planned, do they?

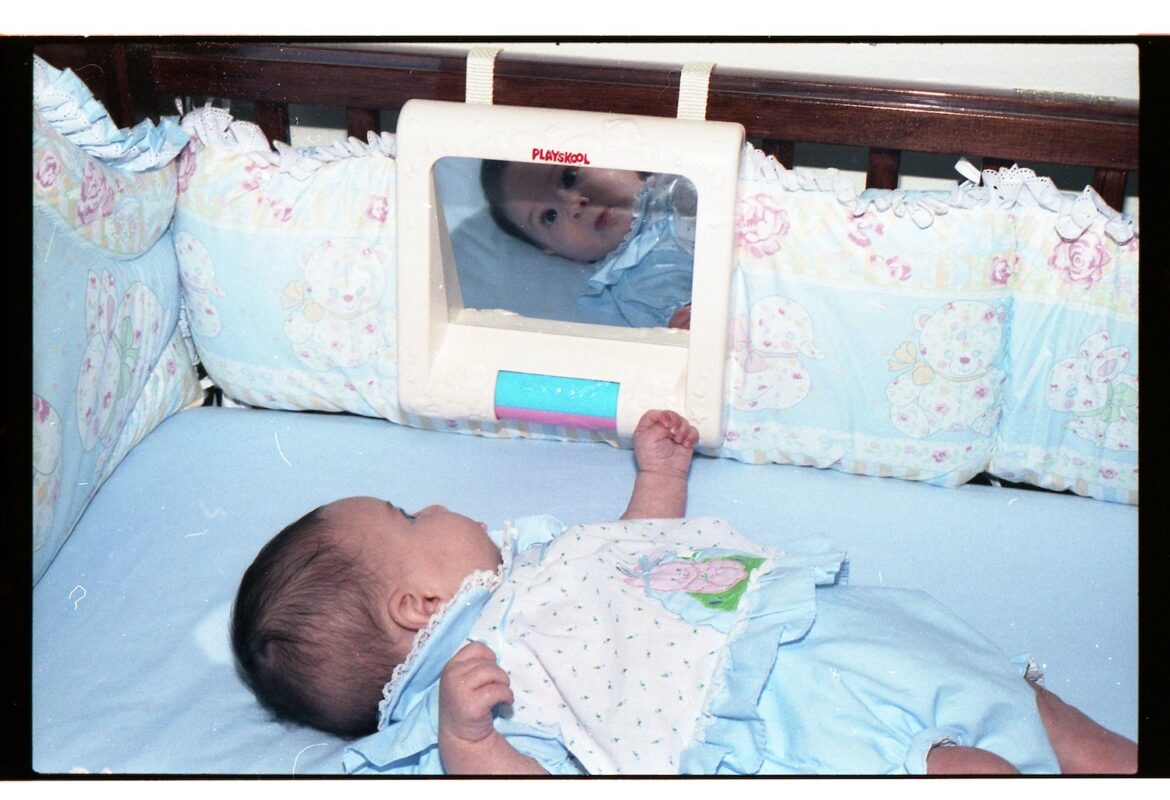

In their defense, nobody told them anything that would make them question their decision. Not the other adoptive parents. Not the agency. Not the lawyers or social workers. Not the church. Nobody handed them books written specifically for their kind of family with bibliographies in the back, nobody said to them that someday their child would scream, “YOU’RE NOT MY REAL PARENTS.” And so they did as they were told and raised the baby as if she had been born to them. But she wasn’t. And they were missing important pieces of the story.

They didn’t know, until she broke down, that anything was wrong at all. How could they have known? The power dynamic was set, whether they meant to build those walls or not. But those walls get built when you buy a human, there’s no escaping it. And so, when she started screaming, they looked at each other and asked, “Is this adolescence?” But that wasn’t the whole picture.

They could have looked for literature, called a professional, asked for help. And, to an extent, they did. They bought Focus on the Family literature and signed their daughter up for therapy and asked their family doctor to diagnose her. But those fixes were only band-aids to a reaction. What was the girl reacting to that made her act this way, feel this way? They should have read the literature for themselves, called a professional for themselves, asked for help for themselves. And maybe it isn’t all their fault that they didn’t do this. What was the adoption agency doing to support them after they’d brought home their child? What literature were they sending? What resources? What support? What advice? None. So, who could the parents really call anyway? Ghostbusters?

These parents got the short end of the stick, too. They were promised a happily ever after. And when everything turned sour and they didn’t know whom to call or whom to blame, they turned on themselves (“maybe we’re bad parents”) and they turned on their daughter (“maybe there’s something wrong with her”) when they should have turned on all of civilized society that thinks adoption is such a lovely thing to do, brave and wonderful on all fronts. So their flavor of embarrassment went from the grief of being unable to conceive to the shame of being unable to parent. And there was nobody to call for help.

Their pain pales in comparison to giving birth to and relinquishing rights to a child or being taken from your mother right after birth. But it is still pain, it is still unfair, and it is the most dangerous pain of them all because out of the three of them, the adoptive parents have the power to lash out, to use their power for pride and strike down the other two characters in this story with an amplified version of the shame they carry themselves. And if they would have had help, if they would have had resources, that could have been avoidable. But that’s not how this story turned out, is it?

But it isn’t the end, not yet. As long as you’re alive, you have the power to make a change, to turn the story around. Out of all the brave things an adoptive parent could do, this is the bravest option of them all.

Shannon Quist is a Texan adoptee and the author of Rose’s Locket. Her master’s thesis on adoptee-written narratives is available on her website. She volunteers with Adoption Knowledge Affiliates, a non-profit that connects individuals, families, and professionals in their adoption journey through lifelong education and support. Follow her on Instagram @shannonrquist.

1 comment

Very good article! So true that if only adoptive parents could find the right resources & help to teach them that a child is not their blank slate because they bought that child. It begins with caring more about what’s happened to others than about themselves.