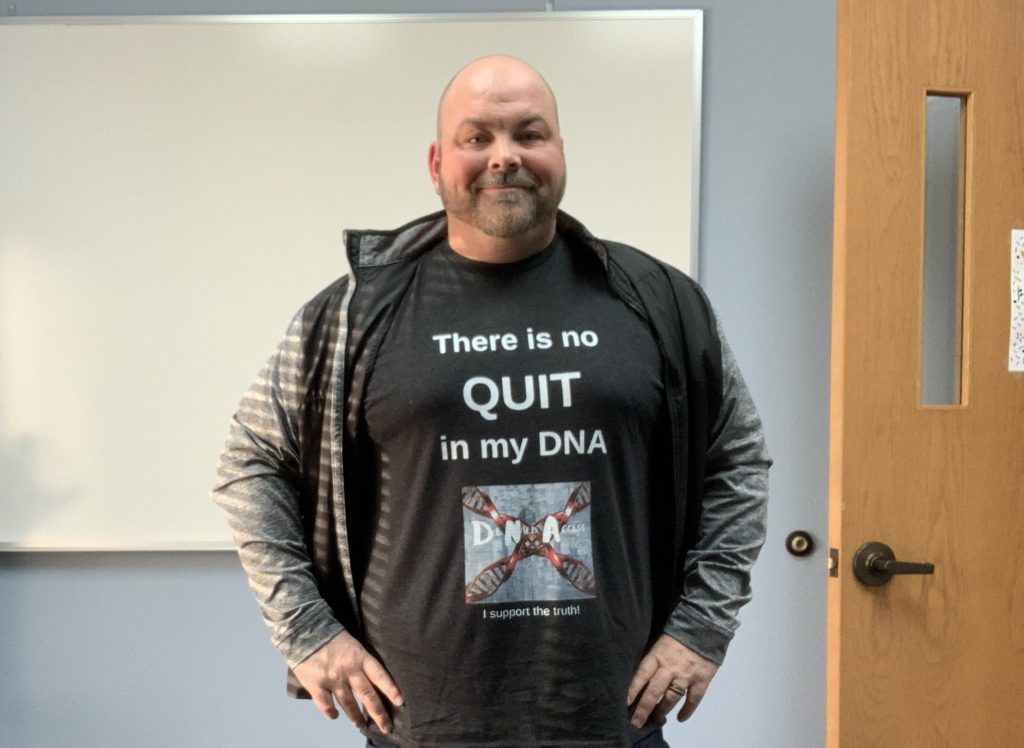

An NPE fights for his right to update his birth certificate.

By B.J. Olson

I was born William Joseph Olson in Sioux Falls, South Dakota on September 27, 1979, when my mother was only 20 years old. Because she’d been intimate with two men, she couldn’t be certain who my father was. One of the men, Brent, had been her senior prom date, and the other, Howard, was eleven years older—a man she saw when he was home on leave from the military. Her father despised him, and though she prayed he wasn’t my father, she suspected he was, thinking she remembered the night I was conceived: Christmas Eve 1978.

Howard had already been married and had a daughter, but my mother believed he was divorced at the time she became involved with him. A dental technician, he was the older brother of my mother’s close friend Alice from high school. During his visits to Lennox, he’d take my mom out on dates, usually to the races. When he wasn’t drunk, my mother says, he was a great guy.

When it came time for my mother to fill in the birth certificate, she chose to leave the father’s name blank. That decision profoundly influenced my life and my self image.

As a poor single woman, she needed state assistance, but the state required her to provide the name of the person who might be my father. She named Brent, but a DNA test ruled him out. That could only mean the man my grandfather despised—Howard—was my father.

When the state agency again asked for the name of a potential father, she then gave them Howard’s name and tried to reach out to him directly before the state would. Howard did everything he could to avoid contact with her. In 1983, she wrote to his commanding officer in the Army, where he was stationed at the time. He wrote back on January 23, 1984 to assure her he would take care of the situation. A week later, she received a letter from Howard’s lawyer telling her not to contact Howard directly again and advising her that all further communications had to be directed to his legal office.

My mother didn’t have the means to hire a lawyer. She’d been under the assumption that since she had to give my father’s name to the state, the situation would be taken care of. It would take the state’s Department of Social Service until August 2, 1996 , when I was just shy of 17 years old, to send a letter to Howard requesting that he take a DNA test to determine paternity.

On January 15, 1997, Howard was finally served papers requiring him to take a DNA Paternity test. The court documents stated that should he be shown to be my father, he’d be responsible for $368 per month in back child support—$79,488—along with half of all medical bills accrued for a problematic birth, tonsil surgery, and a five-day intensive care stay for a concussion I suffered playing football, not to mention all the miscellaneous doctor, dentist, and eye appointments. Another letter, dated March 6, 1997, indicated that he’d be permitted to take the test in Huntsville, Alabama at the Columbia Medical Center and that he wasn’t required to report for the test until April 10, 1997. It took almost six weeks until Howard received a letter from Social Services excluding him as my father.

It was bad enough that my mother was an unmarried woman in a small town, but now, with the only men she’d ever been with ruled out by DNA, she had no clue who my father was. For the next 20 years, she believed she must have been drugged and raped and thus couldn’t recall who the father was. She couldn’t think of another explanation. This had a powerful impact on her, affecting her ability to trust others and contributing to bad decisions in her relationships with men.

I grew up very ashamed of not knowing who my father was. I feared meeting new people who would ask who my parents were. I never had a full answer. People who haven’t experienced this would be surprised how many times you get asked about your dad. I dreaded the first day of school every year when we would have to stand up and tell the entire class about ourselves. I would try to avoid the topic of my father, but it never worked. Until I was 38 years old, I felt my mother was always hiding something from me. I wasn’t sure who she was protecting or trying to protect me from. Naturally, I resented her because I felt she was the reason I didn’t have a dad.

On August 12, 2015, an Ancestry.com commercial lured me into spending $88.95 on what I referred to as my spittoon of hope. Finally, I thought, there was technology that might answer some questions. I was so excited the day the box arrived that I spat in the vial as soon as I was able to muster the saliva. I registered the kit, sent it off, and patiently waited for the results. When at last they came in, my excitement quickly died because there were only distant matches which meant nothing to an amateur like me. I logged off Ancestry.com and once again began to look at every man roughly 20 years older than me and wonder if he was my father.

Nearly three years later, on March 17, 2018, my daughter wondered how substantial our Irish bloodline was, so I logged back in to look at my results. My jaw dropped. I had a new first cousin match, Joanna, whom I didn’t know. I immediately called my mother to ask who the heck she was. A few days later, I received a message through the Ancestry app from Joanna’s daughter, who managed her DNA test. After communicating with her, I learned that Joanna had been raised to believe her grandmother was her mother and her mother was her sister. But in fact, the woman she thought was her sister was her mother. She’d had an affair with Howard’s father when she was very young. Because of her age, her mother decided to raise the child who resulted from that union—Joanna—as her own. Joanna, then, although she didn’t learn about this until much later in life, was Howard’s half sister. The existence of this close match seemed to lend weight to the idea that Howard was my father, but since Joanna was only a half sister, it left room for doubt.

My mother and I were astounded by this discovery and had many questions. We needed to dive deeper. To confirm this Ancestry.com match, my mother reached out to her high school friend—Howard’s younger full sister—who agreed to take a test from Health Street, a Lab Corp company. On April 20, 2018, the results demonstrated that she and I were a 99.9718% relative match.

Although I finally had confirmation about who my father was, I also then knew the sad truth that I’d never get to meet my biological father. If my father had been someone other than Howard, there might have been I chance I could have met him. But Howard had died in Sioux Falls, on April 5, 2010, less than 10 miles from where I lived at the time. Immediately I was angry and I wanted more answers!

Once I knew I was certainly related to Howard, I felt more confidence about contacting his famiIy. I knew he had a daughter and I reached out to try to find out more about him and to see if she’d take a test that would further confirm that we were siblings. Within minutes of receiving my message, she emailed me the original 1997 DNA test results from her deceased father and asked me not to contact her again. It struck me as odd she responded so quickly and happened to have that documentation, which I now knew was erroneous, at the ready.

Since I got nowhere trying to get information from my sister, I thought I’d connect with other members of my biological family. I’d known these people all along. Lennox was a small town of roughly 1,000 people when I grew up there. My family owned the local hair salon. Everyone knew everyone. Howard’s mother—whom I now know to be my grandmother—was our cleaning lady. His brother was our garbage man. His sister-in-law was my music teacher. The catcher on my baseball team and a classmate throughout all four years of high school were my cousins. I had relationships with all of these people prior to knowing that Howard was my father. Once I’d made my discovery, they all shut me out.

I had uncovered a big secret that no one wanted to talk about. The family had a pact, created by Howard’s closest brother Harry, to avoid all contact with me and my mother. Except for Joanna, all family members I discovered ultimately rejected me.

Even though all signs led to Howard, I continued to seek further evidence that he was my father. Since my relatives wouldn’t cooperate, I hired a genealogical private investigator who tracked my ancestry back a couple hundred years. The genealogical trail led to the same conclusion as did the DNA—that my ancestors were Howard’s family. It indicated that my grandparents were Howard’s parents, which meant that one of their sons was my father. But, like Howard’s daughter, none of his brothers would speak with me.

After I hired the investigator, Howard’s daughter sued me for $50,000.00 in the state of Texas for invasion of privacy and for stating that Howard had an illegitimate son. She noted this caused her and her family anguish. Just as her father had decades earlier, she tried to use lawyers to silence me.

I did not cave. I fought back to have her drop the suit. After I spent several thousand dollars in lawyer fees she finally did, and I made it clear to the family that I will not let this rest until I get the answers I deserve.

I’m not looking to expand my family, get invited to more family events that I don’t have time for, or even to take my father’s name. I just want an identity. I want my story to be known. I want to draw attention to the errors and deception that affect how vital records are created and maintained and assert that we should have the ability to correct vital records based on science.

I have been denied access to my father’s family history, his military benefits, and his medical history. I will continue to use my loud voice until I can make a change for everyone whose rights have similarly been denied. I intend to work to bring awareness about the situation of NPEs—to change laws to give NPEs the right to correct their birth records based on scientific evidence.

Since I have come forward with my story on my Facebook page @deniedaccessDNA and website DeNiedAccess, dozens of people have come forward to share similar stories. I’m not alone in this battle, and I look forward to the day when people realize the truly innocent victims are the those who did not ask to be born and who are just trying to clean up everyone else’s mistakes. There is no QUIT in my DNA!!!