How do you explore your new ethnicity when a DNA test—in the middle of a global pandemic—tells you you're not who you thought you were?

By Jess Kent-Johnson

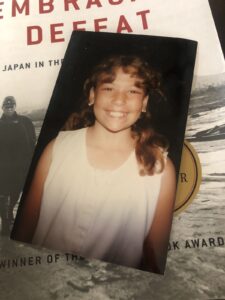

I radiate a warm glow in the photo—a farmer’s tan from hours of playing outside in the Texas sun. A neighborhood friend had documented the moment via disposable camera. It’s hard to remember what occasion we were marking—an eleventh birthday party, perhaps, or the end of the school year. Whatever the event, my smile is wide, genuine, and my brown eyes are scrunched into happy almonds in a heart-shaped face.

This photo never meant anything special to me then, but now I wonder how could I—how could my family—not have questioned my true heritage? I’m 34 years old and I’ve just discovered by way of an at-home DNA test that I’m 25% Japanese. This revelation launches me into a frenetic investigation—activating an old Ancestry.com account, sending cryptic text messages to my parents and brother, and diagramming possibilities on the back of a napkin.

After all, my maiden name sounds like a type of sausage, and Mom is a freckled redhead, clearly the offspring of Scottish-Irish farmers. Growing up, I’d never been questioned about my whiteness, although there were comments that I tended to tan in a more olive tone than did my younger brother. Since we played outside for 6 hours a day in the southern heat, no one thought twice about it.

After hours of frantic speculation, I get a text message from my mother, with whom I have shared the surprising ethnic breakdown. She says, “Can I call you later?” It’s on this phone call that she shares the truth—there was an ex-boyfriend who was half-Japanese just before she and Dad got married. She’s Googled him to find an obituary from 2012. He’s survived by a brother, a wife, and his Japanese mother. Mom sends me the link.

The need for information consumes me. Through the names and locations in the obituary, I construct a new family tree at Ancestry.com, searching through other public trees for details or connections. I message someone who has posted a photo of herself at my biological father’s wedding—it turns out she is his sister-in-law. She puts me in touch with my surviving uncle in Texas—states away from my current home in Wisconsin. Initially he’s generous with details and sends a few photos of my father and grandmother. After a few months, however, the connection trails off. He claims to be busy with other family affairs. I’m cautious. I try not to ply him with too many questions, afraid that I may fray the tenuous connection we’ve had thus far. He tells me that while my grandmother is still alive, she has severe dementia and has completely lost her sight. I might never meet this woman, and even if I do, it’s potentially damaging to her to explain the circumstances of our relationship. I try not to be dismayed. The facts he shares: my grandfather was a GI in World War II, he and my grandmother met in Japan, they married and divorced, and my grandfather died in a tragic farming accident.

So what’s a girl to do when she’s been flung out into the ether, isolated and spinning without any tether to who she is? Ordinarily, I might visit cultural festivals or historical societies, or enjoy cuisine from my new culture at a traditional restaurant. Unfortunately, I’ve learned this ground-shaking news amid a global pandemic, during which survival requires that I keep a distance from both strangers and friends.

Instead I use Ancestry.com to find the ship manifest that shows my grandmother’s departure from Yokohama in 1952 and her arrival in San Diego. She was 22 years old. I search for books about World War II and its aftermath in Japan and discover John W. Dower—a historian who has written extensively about America’s occupation of the island nation. Japan had been racked by air raids, poverty, and a diminished population of young Japanese men. GIs were friendly and laden with chocolate or cigarettes to share. Women who married these men became “Japanese war brides.” I understand the allure of traversing the ocean for the possibility of better prospects.

From each book I keep a meticulous list of hyperlinks, notes, bibliographies—following these details like bread crumbs that will lead me home. My research leads me to a documentary, “Fall Seven Times, Get Up Eight,” the story of war brides who endure the otherness of being Japanese in an American world. Their families in Japan often discouraged them from marrying American men. They dealt with U.S. segregation and the bitterness of Japanese Americans who had survived U.S. internment camps and perceived the women as entitled and lazy.

I form a composite picture of my grandmother based on similarities among the women of the film. All have done the best they could to survive, learn English, work, and raise children in an unfamiliar land, the side effects of which were often domineering personalities, high expectations, and subdued emotion.

The cocktail of emotions I experience as I pore through these resources is jarring. Some days I grieve that I can only conjecture whether my grandmother’s personality aligns with the women in these stories. My uncle is not yet willing to share more intimate details of their childhood, and my mother has no more information than what the Internet provides.

In other moments, I wonder if I should feel relief that I will never meet my grandmother. What if she was unwelcoming to me, scarred too deeply by past trauma to extend empathy to an adult granddaughter born out of wedlock? In these fraught moments, I look back at my childhood photo—the smiling, carefree daughter—and I try to still my mind with gratitude. I may not have first-hand knowledge of this person and the culture from which I’ve sprung, but I do have courage. Perhaps the best way I can emulate my grandmother is to continue my own voyage into a culture I’ve never known.

Jess Kent-Johnson is a writer, actor, and musician. She lives in Madison, WI with her husband, Alex, and dog, Arrow. Find her at www.jesskentjohnson.com or on Instagram @surelyyoujesst.

Return to our home page to see more essays and articles about NPEs and DNA surprises. And if you’re an NPE, adoptee, donor-conceived individual, helping professional or genetic genealogist, join Severance’s private facebook group.

BEFORE YOU GO…

- Please leave a comment below and share your thoughts.

- Let us know what you want to see in Severance. Send a message to bkjax@icloud.com

- Tell us your stories. See guidelines at https://severancemag.com/submission-guidelines/

- If you’re an NPE, adoptee, or donor conceived person; a sibling of someone in one of these groups; or a helping professional (for example, a therapist or genetic genealogist) you’re welcome to join our private Facebook group at https://www.facebook.com/groups/402792990448461

- And like us on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/severancemag and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @Severancemag