What ethical obligation do you have to the biological family you've never met?

By Amy Goldmacher

This year I turn 48, the age my father was when he died of pancreatic cancer. So I had a genetic test. I wanted to know if there was a reason to worry I might get—or have—cancer. I already know I have risk factors: an immediate family member who died before the age of 50, and I have Ashkenazi Jewish heritage on both sides.

A desire to foresee my fate, to know my destiny, opened a Pandora’s box. In order to get a genetic test, I was required to receive counseling first, to understand how genes work, what risk factors I may have, to decide whether I really want to know if something deleterious is waiting for me.

In our session, the counselor talked me through genes and inheritance. On a piece of paper, she drew a genogram, a family tree with symbols depicting gender and relationships, known cancers, and deaths.

“In anthropology, we call that a kinship chart,” I told her. As an anthropologist, I was familiar with these models. Kinship diagrams show relationships. For anthropologists who go to live in foreign cultures, it’s a tool to reduce confusion between common names in the community of study. It’s a way to map a community, as relationships between people impart more meaning and contextual information than does an individual.

My genogram only had ten symbols on it. Ten known family members, five of whom were deceased. The genetic counselor wrote the words “limited info” on the paper depicting my family. “That was quick,” she said. “You don’t have a lot to go over because you don’t have a lot of family.”

A 2019 PEW Research Center survey found that 27% of home DNA test users discover unknown close relatives, meaning a person could accidentally learn they are not biologically linked to those to whom they thought they were related. DNA tests can have devastating emotional consequences when people learn they have no genetic connection to their kin.

But I was in the inverse situation: my genetic test results impacted biological relatives to whom I had no actual connection.

My father had estranged himself from his family of origin when he was in his early thirties. He cut off all contact with his mother and two younger brothers by the time I was eight. (His father had died by then, due to heart-related issues, as far as I know.) I don’t know why he did it, but as an adult reflecting back, I think disconnecting was what my father felt he had to do to survive.

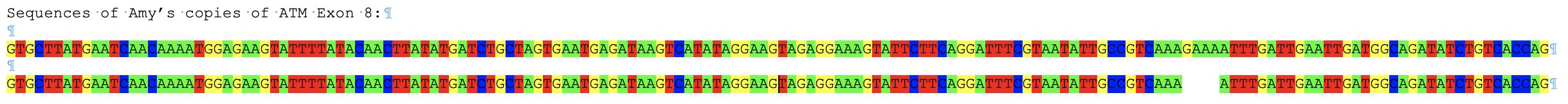

Forty years later and 26 years after my father’s death, I had the test and learned one copy of my ATM gene has a pathogenic mutation, an alteration with sufficient evidence to be classified as capable of causing disease.

The abbreviation ATM stands for “ataxia-telangiectasia mutated.” The ATM gene is located on chromosome 11. It helps control cell growth and repair and replace damaged DNA. Research suggests that people who carry one mutated copy of the ATM gene may have an increased risk of developing several types of cancer. Those who carry ATM mutations experience more frequent cancers of the breast, stomach, bladder, pancreas, lung, and ovaries than do others, but studies are neither definitive nor conclusive. Research is ongoing, and guidelines and testing protocols are updated every year as new information is learned. The gene wasn’t even discovered until 1994, the same year my father died.

There is justification for worry. In 2020, pancreatic cancer was the third leading cause of cancer deaths in the US—surpassing breast cancer—and is on the rise. Pancreatic cancer has a very low survival rate. Symptoms are generally not detectable in early stages; by the time it’s found, it’s usually so advanced that treatment and surgery have little benefit. Some research shows chemotherapy may extend life only by days or weeks, and the quality of that extra time is not good. The median survival rate is three to six months.

It’s a short distance from pancreatic cancer diagnosis to death. Recently we mourned the losses of “Jeopardy” host Alex Trebek, civil rights legend John Lewis, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and, not that long ago, actor Patrick Swayze, to pancreatic cancer.

My father lived 16 months past his diagnosis. He endured surgeries, radiation, and chemotherapy and suffered their ravages. I saw him lose his ability to walk, see, eat, speak. He exceeded expectations, but it was a long, slow slide to the inevitable, and we had that much more time to watch him suffer with helpless dread. I was with him as he died. The grief from that loss is still with me today.

I assumed, as did my genetic counselor, that my mutation was inherited, not caused by something in the environment, even though only 3% to 10% of diagnosed cancers are heritable.

The only way to know for sure would be to fill in my genogram, my kinship chart, with more information from living family members: my father’s brothers—my uncles, who were, in effect, strangers.

Genetic testing for pathogenic mutations in family members can be helpful in identifying at-risk individuals. What was my obligation to my biological relatives? If not to my father’s estranged brothers, what about their adult daughters? There’s a 50% chance they inherited a mutated gene that increases their risk for cancers, and if they have it, their children have a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation as well.

These women are strangers. I never met them. I don’t know if they know I exist or if they knew they had an uncle who died. But the genetic information is important; I would want to know if there was something in the biology of a stranger that affected me.

I searched for my cousins’ addresses on the Internet so the genetic counselor could send a letter: “A member of your family has been identified as having a mutation in the ATM gene….”

I asked the genetic counselor to include my contact information and how we are related in the letter so my cousins could reach out to me if they wanted. She informed me it’s against policy.

Robert Kolker, author of “Hidden Valley Road,” suggests genetic ties are but one aspect of how we connect to others: “We are more than just our genes; we are in some way a product of the people who surround us, the people we’re forced to grow up with and the people we choose to be with later. Our relationships can destroy us, but they can change us too and restore us, and without us ever seeing it happen, they define us. We are human because the people around us make us human.”

I wanted to do a good thing, the right thing. But maybe I can’t make a familial connection out of a biological one.

Amy Goldmacher is an anthropologist, book coach, and author in Michigan. Visit her website and find her on Twitter and Instagram @solidgoldmacher.

BEFORE YOU GO…

Look on our home page for more articles about NPEs, adoptees, and genetic genealogy.

- Please leave a comment below and share your thoughts.

- Let us know what you want to see in Severance. Send a message to bkjax@icloud.com.

- Tell us your stories. See guidelines.

- If you’re an NPE, adoptee, or donor conceived person; a sibling of someone in one of these groups; or a helping professional (for example, a therapist or genetic genealogist) you’re welcome to join our private Facebook group.

- Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @Severancemag.