By Megan Culhane Galbraith

Once upon a time a little girl was born in a charity hospital in Hell’s Kitchen to an unwed mother.

Her name was Gabriella Herman and she was adopted about six months later. Her name was changed and her identity was erased. Her birth certificate was dated two years after she was born.

By the time she was six months old she’d had three mothers: a birth mother, a foster mother, and an adoptive mother.

_____

My reunification with my birth mother began via a letter from Catholic Charities followed by another by Air Mail from my birth mother. To me it felt like a new beginning. Perhaps then it is fitting that our relationship would end with a letter. This time it was sent 25 years later and by certified mail.

_____

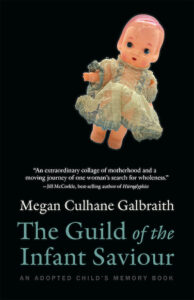

The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book is my attempt at unwinding the story of my birth and identity through the lens of stories told to me by my birth mother. The book was accepted for publication on Mother’s Day 2020. The synchronicity was not lost on me. My debut! My first-born! My book baby! My mother—dead for decades—wasn’t here to celebrate my happy news, so I called my birth mother to tell her my book was about to be born.

She was excited for me on the phone. She mailed me a congratulatory card. Inside she wrote; “You did it! Congratulations on getting your book in print in 2021. How wonderful! XOX.”

She was fond of using the USPS and had a habit of sending me envelopes stuffed with news clippings, Harper’s articles she’d torn out of the magazine, and typed letters that contained sternly worded directives even though I hadn’t asked for her advice. I called these her “lectures.” I shrugged them off in the interest of maintaining a relationship with her. After all, she was the only mother I had left.

_____

I use dolls as a window into my story by recreating photos from my baby book in my dollhouse. Doing this allowed me some distance from my fears. By playing with dolls I could examine those fears through a different lens. Dolls are used to understand trauma in myriad ways—“show me where he touched you,” or “point to where it hurts” or “can you show me where she hit you?”

Memory born from trauma is full of dead ends. Shame is spring-loaded. My birth mother’s stories circled back on themselves: they were versions of a truth.

When I brought up the shame and the trauma I felt as an adoptee, she said they were useless emotions.

_____

As I dove into editing my book I sought permissions from my father, my siblings, and my birth mother to use various photos from my baby book or, in my birth mother’s case, from the album she’d given me titled “Our Family Album.” These were photos of her as a teenager, in her early 20s, and of our reunion in New York City, at a hotel just blocks away from The Guild of the Infant Saviour, the Catholic unwed mother’s home where she’d been sent to have me.

Dad gave his immediate approval: “No one can tell your story but you, honey,” he said. One of my siblings supported me; the other did not.

After weeks of unusual silence from my birth mother I became concerned. My follow-up emails were met with what felt like chilly silences. When she finally wrote back her tone was cold.

“I sent you a letter about permissions,” she said. “You need to go to your local post office to investigate.”

“Need” and “investigate.” Those words sent me into a spiral of anxiety.

In the early stages of my search for her I’d used the number on my birth certificate to compare with the numbers in the genealogical listings at the New York Public Library. It was an exhaustive and fruitless effort. Now, she was asking me to search again, but without a USPS tracking number I was at a loss. It was like I was setting out on another search but this time without even a number as a clue.

_____

I began thinking about silences. I re-read Silences, by Tillie Olsen.

THE BABY; THE GIRL-CHILD; THE GIRL; THE YOUNG WRITER-WOMAN

“We cannot speak of women writers in our century (we cannot speak of some in an area of recognized human

achievement) without speaking also of the invisible, the as-innately-capable: the born to the wrong circumstances—diminished, excluded, foundered, silenced,” writes Olsen.

“We who write are survivors . . .”

_____

Many emails later, my birth mother forwarded the USPS details to me. As I clicked through the tracking system I realized she’d sent me a certified letter. I was stunned. It had been undeliverable for nearly a month and was now on its way back to her marked, “Return to Sender.”

_____

re.turn | \ ri-ˈtərn

intransitive verb

1. to go back or come back again //return home

transitive verb

2. give, put, or send (something) back to a place or person

sent\ ‘sent\; sending

transitive verb

1. to cause to go: such as

a. to propel or throw in a particular direction

b. DELIVER //sent a blow to the chin

2. to cause to happen //whatever fate may send

3a: to force to go: drive way

b. to cause to assume a specified state //sent them into a rage

_____

A wise friend of mine told me her experience with book publishing was 90 percent wonderful and 10 percent “a blow to the head you never saw coming.” Here was my 10 percent. I felt physically sick for days. I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t eat. I felt nauseated and deeply lonely. The two people most opposed to me using my voice were the two most closely connected to me by adoption.

Why a certified letter? Why such an abrupt change in tone? Why the long silence and sudden secrecy? What had changed in the days between our upbeat phone call, my birth mother’s congratulatory card, and this letter? Why couldn’t she have returned my phone calls?

“Can you please email me the contents of the letter?” I wrote.

“After two failed attempts by the U.S. Postal Service to deliver this May 22, 2020, certified letter to you, I have no choice but to send it by e-mail,” she wrote, copying my editor and the series editor.

Before she’d grant me permission to use the three photos she’d need to read, revise, and edit my entire manuscript, she said. She suggested there were inaccuracies. She requested her privacy.

“I hope that you will have the honesty and integrity to grant this request,” she wrote.

Was she trying to keep my book from being published? Why was she making this about her? I felt like she was trying to silence me just at the time I was finding my voice.

_____

The search for my birth mother began nearly 25 years ago via a letter from Catholic Charities that contained her “non-identifying information.” From those spare details, plus a search by my caseworker, I found her. She’d been willing to be found. We began a long-term relationship. She’d promised to be my open book. She’d said I could ask her anything. I listened to her stories and wrote a book about piecing together my identity via her memory, among other things.

She’d surrendered me when she was 19 years old. We’d done the hard work of knitting each other into our families. Now she was demanding I erase her from my narrative.

How could I choose a name for her that would signify this second erasure, this silencing?

_____

erased; erasing; erasure

transitive verb

1a. to rub or scrape out //erase an error

b. to remove written or drawn marks from //erase a blackboard

c. to remove (recorded matter) from a magnetic medium //erase a videotape

d. to delete from a computer storage //erase a file

2a. to remove from existence or memory as if by erasing

b. to nullify the effect or force of

_____

Fairy tales fascinate and annoy me because of the lack of agency of the female characters. The women are acted upon, locked away, shut up, and shut down (many times this involves a wicked stepmother.) They wait for permission to speak, or for a prince to rescue them.

In deciding on a pseudonym for my birth mother I was firm that I would not erase my birth name, or our shared last name. I’d had enough of the shame, secrets, and half-truths that burden us adoptees. The shame wasn’t mine to carry anymore. If she wanted to live in the shadows, so be it.

I’ll rename her in my book I told my editors, but I won’t erase myself in the process.

I chose the name Ursula. It reminds me of another tale; that of Ursula the Sea Witch in Hans Christian Anderson’s 1836 version of The Little Mermaid. Ursula demands the little mermaid’s voice in exchange for fulfilling her desires.

“But if you take away my voice,” said the little mermaid, “what is left for me?” goes the tale. … “Put out your little tongue that I may cut it off as my payment …” says Ursula.

_____

In his column for Catapult called “Love and Silence,” my friend and fellow adoptee Matt Salesses writes about how hard it is to tell a story the narrator is not supposed to tell.

He teaches Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior. He writes:

“. . . begins with a story the narrator is not supposed to tell. It is the story of her drowned aunt, who was erased by her family because her story is unacceptable: She became pregnant out of wedlock. In punishment, the townspeople burned the family’s crops and killed their livestock, and the next day, the aunt was found with her baby in a well. The narrator, Maxine, is told this story by her mother, on the day she gets her first period.

“Beware, the story implies, of desire. The narrator’s retelling of her mother’s story doesn’t censor desire, but explores it, wondering whether the baby was a result of rape or love, why the aunt did not abort it, why she jumped into the well with it—a kind of mercy? The retelling is an act of love. Maxine frees her aunt from erasure, by making the story-that-should-not-be-told (which is always only one story) into many stories, reinstating her aunt in the realm of imaginative possibility.”

The retelling is an act of love … in the realm of imaginative possibility.

_____

One of Ursula’s favorite books was Diane Setterfield’s The Thirteenth Tale. I have the copy she gave me here in my lap. I’ve read the novel many times. It was Setterfield’s first published book.

The narrator is Margaret Lea—whose name is near perfectly similar to my birth mother’s. In the novel, Lea admits to feeling like half a person who is compelled to unwind the narrative threads and the secrets of a reclusive writer named Vida Winter. Winter tells her dark family story through Lea, who is not allowed to ask questions.

The epigraph of the novel reads:

“All children mythologize their birth. It is a universal trait. You want to know someone? Heart, mind, and soul? Ask him to tell you about when he was born. What you get won’t is the truth; it will be a story. And nothing is more telling than a story.”

—Vida Winter, Thirteen Tales of Change and Desperation

The Thirteenth Tale is a story about endings as much as beginnings. It is structured to begin where it ends because, in the end, both characters confront the weight of family secrets, their pasts, and their intersecting stories. Its themes are identity, loss, reconciliation, and death.

I’m unsure what compelled me to pick up the book again except the vague memory that it was a book about a book about memory, and that it was significant to my birth mother. When I first read it years ago, I’d wondered if she was trying to tell me something. It felt like a harbinger. Just like the main character, Ursula had been telling me stories about my birth and her life for years. Many times she bristled at my questions and shut me down.

“The past is the past, just leave it there.”

“Whose memoir are you writing, mine or yours?”

The end always justifies the beginning.

_____

I have a poem by Lucille Clifton secured to my refrigerator titled, “why some people be mad at me sometimes” …

“they ask me to remember

but they want me to remember

their memories

and I keep on remembering

mine.”

_____

Most fairy tales have a “happy ending,” but that rarely happens with adoption. Have we come to the end of our story? Is this what is meant by “coming full circle?”

I was born. I was surrendered. I was adopted.

We were reunited: lost and found and lost.

It’s been nearly a year of silence from her. My book will be born on almost the same day one year after she sent me that certified letter.

I must now be the one to surrender.

THE END

Megan Culhane Galbraith is a writer and visual artist. Her work was a Notable Mention in Best American Essays 2017, has been nominated for two Pushcart Prizes, and has been published in Tupelo Quarterly, Redivider, Catapult, Hobart, Longreads, and Hotel America, among others. She is associate director of the Bennington Writing Seminars and the founding director of the Governor’s Institutes of Vermont Young Writers Institute. Look for her on Twitter, on Instagram here and here, and on Facebook here and here. Go here to buy signed copies of The Guild of the Infant Saviour and for information about events and interviews.