By Pamela K. Bacon

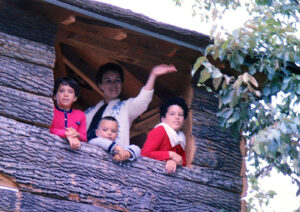

Laurie, Randy, and Pam with their mother

For as long as I can remember, I felt different, as if I didn’t belong. I was the oldest of four children growing up in suburban Detroit. My teenage years were an emotional roller coaster full of the usual twists and turns of adolescence multiplied by my struggle to sort through the isolation of feeling like an outsider in my own family. It became clear to me that the father I lived with was not my father, so I tried very hard to keep those feelings buried away. Did I mention I hate secrets?

A few years ago, a good friend gave me a 23andMe test kit for my 62nd birthday. I was a nurse, and she was a doctor, and as both of us were getting up in age, the topic of health topped our conversation during our daily walks. She’d done a test herself and was amazed at the health information she now had a window into. I prepared my test and sent it for analysis.

Little did I know that my results would open a whole other window of enlightenment. I received not only health information but also the names of DNA matches. Several close relatives showed up in my list of matches right below the siblings I grew up with. They were familiar names to anyone who grew up in the Detroit area back then, but not as a part of my family as I knew it growing up. The pieces were coming together, but my courage to complete the puzzle was still lacking.

In 1984, a few years after my first child was born, the father who raised me died at 53 of a sudden heart attack. In the hectic days of planning and having his memorial service, my siblings and I had time to share memories as we looked through the paperwork and gathered documents for insurance and Social Security and took care of other details that needed attention after an unexpected death. In February, while sorting through our family’s important papers, we discovered a discrepancy between the year on my birth certificate and the year listed on our parent’s marriage license. I was born in 1955, and my parents were married in 1956. That seemed strange, but there was a funeral to be held, so we moved on.

Not too long after my father’s death, I got a big boost of courage and decided to confront my suspicions head on. I was a mother myself then in my late twenties with a young son. The desire to learn the truth was still burning inside of me. I’d never seen a picture of my dad with me when I was a baby. Come to think of it, I don’t remember any pictures of me as a toddler or a young child. I don’t think there were any. My mom seemed surprised the morning I asked her if dad was my “real” father. She asked me to get something from the silver file box that held our family’s important papers.

A homemade card caught my eye—a birth announcement that proudly stated “A King is Born.” I remember my initial feelings of joy to think that maybe I had been wrong about feeling different all these years. My joy was short-lived though as I opened the card to discover it wasn’t celebrating my birth. The new King referred to my sister Laurie, who was born 22 months after me. No one does that for their second child I remember thinking to myself, I was not a King.

I returned to the kitchen table wiping away a few tears as I approached mom clutching the birth announcement in my hand. “How did you know” my mother asked. I told her that I had always felt that something was not quite right and that I hadn’t felt close to dad most of my childhood. It was something I’d kept to myself about because I was afraid of the consequences of what I might discover. “What can you tell me about my father” I muttered. She hesitatingly opened the window a bit for me that afternoon.

Mom grew up in Detroit as the oldest of six kids. She dropped out of Cooley High School in Detroit to help the family with bills while working the counter at the nearby Sanders Confectionary and Ice Cream Shop. After work, she loved to escape to the dance halls scattered around downtown Detroit to listen to the all the great entertainers that passed through. It was the winter of 1954, and she was 19 years old.

Mom said that she had a friend named Mario who frequented the neighborhood bar and pizza place. He was a boxer with a contagious personality—a friend to everyone he met. Mario looked out for my mom as a big brother would. One evening when they were hanging out, he introduced her to his buddy Mike, a nice-looking guy a bit older than she who played minor league baseball.

Mario, who was Italian, thought it was funny that Mike, who was obviously not Italian, was obsessed with pizza. “All he wanted to do was learn to make pizza” Mario later told me, so much so that he spent the off season from baseball perfecting his craft. “Your father’s name is Mike, the pizza man” my mom blurted out. That pronouncement landed like a lead balloon on my heart. All these years of wondering who I was and then this. A name. Mom didn’t really want to talk about it anymore, and I decided to leave it at that.

The birth of my first grandchild in 2015 brought back all those childhood memories of feeling that I didn’t know myself completely. My mother had passed away two years earlier, but I still had a desire to fill in the blanks. I had a strong desire to tell my son a bit more about the family secret that I had kept hidden from my own family all these years. Later, when my DNA test results revealed names that matched what my mom had told me, I mustered the courage to take another step in the discovery process.

At a family gathering in northern Michigan, I pulled my brother Randy aside. As we sat on the beach overlooking Lake Huron that summer afternoon, I shared my story and DNA test results. He was shocked at first but said that he had always thought I had been treated differently by our dad. We joked as kids that we didn’t really look like each other, and Randy had maintained that his father was probably the Twin Pines Milk Man who always seemed to linger at our house when mom was around! He never suspected that I was the one with a different father.

Randy had been doing genealogy research for quite some time on our family and was certain he could help put all the pieces together. He explained that there were multiple matches that were considered “close” relatives to me that were not common to his results. The decision to finally share with him what I had hidden away and struggled alone with all these years would connect the dots on the secrets that my mother and I had danced around for more than 60 years.

Armed with my DNA records from Ancestry and 23andMe, my brother dug into the research while I reached out to some of the higher cM number matches at the top of my list. Our goal was to confirm the identity of my biological father and gain medical and family history for me, my son, and future generations. He shared with me each discovery along the way as the picture became clearer.

Our first stop after reaching our conclusion that Mike was my father was to reach out to The DNA Detectives, created by CeCe Moore, an expert genetic genealogist who’s consulted on and appeared in many DNA specials including the PBS documentary series Finding Your Roots and more recently helped solve cold cases using genetic genealogy on the ABC series The Genetic Detective. Randy shared the information with her team, hoping her search angels could confirm our conclusion. They were incredibly helpful in building out my tree on my birth father’s side using the science of DNA results, which clearly confirmed our suspicions. Professional genealogists from Ancestry and Legacy Tree Genealogists independently came up with the same results.

I also heard back from a DNA match not long after I had initially reached out to her via email. I was hoping she could shed some light on her family and how I might fit in based on our match. She replied enthusiastically, which was a bit of a relief. She was a first cousin once removed on my father’s side, and she proclaimed “we might even have to throw you a party” in her note, saying that she had a wonderful family. I tried not to let myself get too hopeful at how welcoming and open she was, so I let some time pass before reaching out again, although I couldn’t stop thinking about her.

I shared my conversation with my brother, who was thrilled that I’d made contact and that I’d found a relative on my birth father’s side. He urged me to stay engaged with her and reminded me that I had waited all these years to open myself up to this journey, so there was no need to tiptoe around anymore. “This is your personal history, and you deserve to know” he repeated each time we spoke about it.

I called again and was relieved to get that same affirming response from her. We talked for an hour and determined that another match who listed at the highest number of cMs was her uncle and my first cousin. She confirmed that her grandfather had a brother named Michael. Mike the pizza man! I’d gotten my DNA confirmation, and now I had a new family member who confirmed my connection to the family name.

Mike was a legendary favored son in Detroit and he and several of his children were public figures with a well-known story that matched what my mom had alluded to years before. Unfortunately, he’d passed away a few years earlier in 2017, but I was able to read quite a bit about him and his accomplishments. In November 2019, I reached out to one of my newly discovered half-sisters, and we had a few good conversations via phone and text. We even talked about meeting sometime, but then she fell silent. Months passed with no response. I eventually reached out formally via a mediator who specialized in these matters and received word back that the family did not have any interest in me or my story.

Although this was not the reaction I’d hoped for from the family, I finally knew the rest of my story. My family tree was complete for me, my son, my grandchildren, and generations to follow. I’d pictured how this might turn out. I’ve seen and read so many stories of reunions with happy endings after DNA surprises, such as that of the Duck Dynasty patriarch who acknowledged and met with his adult daughter discovered through a DNA test or the GMA story of an Army general and colonel who recently reunited with their half-siblings after 50 years. I hope that someday I, too, might be acknowledged by my half-siblings. It’s a basic human need to know where you came from and to be able to tell your story. There are constant reminders of that missing piece of my heart each time I pass by one of the family restaurants or read another news story about the family.

For my parents and those from earlier generations, there was shame associated with a child born to a single mother. My mother had talked about being hidden away by her family while she was pregnant with me and how difficult it was for her during that time. Although my mother and Mike had done nothing wrong—neither was married—my mother was forced to go to the Florence Crittenton Home for unwed mothers in downtown Detroit, where I was born in August of 1955.

The social stigma surrounding a child born out of wedlock has diminished over the years as generations have evolved, but it still exists. There are many like me who get rejected. We are left to feel as if we have done something wrong or that we should be ashamed of our history. I am still in contact with a few family members on my half-uncle’s side who have acknowledged me. And from all that I’ve read about my birthfather, I’m certain he would have welcomed me with open arms if only I’d discovered him in time. That’s what his public persona was—kind, giving, and people first. It’s not the Hollywood happy ending I envisioned over the years, but I hope that my half-siblings and I might still have the opportunity to get acquainted.

Pamela King Bacon is a registered nurse from Portage, Michigan, and a proud grandmother of two grandchildren. She and her brother, Randy King, are working on a documentary about her story and their mother. You can reach her at pikbacon@icloud.com.