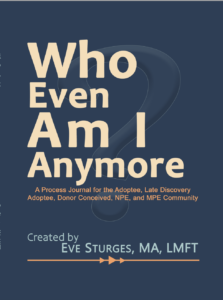

If you’ve made a shocking family discovery, it likely threw you off balance, maybe even knocked you down. You may have been—may still be—bewildered, angry, hurt, confused, anxious, depressed, or ashamed. You may have experienced all of these emotions and others in succession, all at once, or in an unpredictable pattern. You may feel overwhelmed and unable to make sense of all the feelings and at a loss about how to communicate your thoughts. That’s why licensed therapist Eve Sturges created Who Even Am I Anymore: A Process Journal for the Adoptee, Late Discovery Adoptee, Donor Conceived, NPE, and MPE Community. Host of the popular podcast Everything’s Relative with Eve Sturges and an NPE (not parent expected) herself, she’s deeply familiar with the many ways the revelation of family secrets can sideline a person. It’s not a substitute for therapy, nor was it intended to be, but this first-of-its-kind journal is just the tool many need to help them on this unexpected journey; and for those who are in therapy, it can play a role, helping them think about their reactions and improving their ability to articulate their feelings. Sturges doesn’t provide answers. Instead, she offers prompts to stimulate your thoughts and kickstart self-expression. She asks questions and provides a safe space in which you can explore the answers, either privately, within a group, or with a therapist. Deceptively simple, it’s a crucial resource that’s certain to make a difference for thousands of NPEs and MPEs.

If you’ve made a shocking family discovery, it likely threw you off balance, maybe even knocked you down. You may have been—may still be—bewildered, angry, hurt, confused, anxious, depressed, or ashamed. You may have experienced all of these emotions and others in succession, all at once, or in an unpredictable pattern. You may feel overwhelmed and unable to make sense of all the feelings and at a loss about how to communicate your thoughts. That’s why licensed therapist Eve Sturges created Who Even Am I Anymore: A Process Journal for the Adoptee, Late Discovery Adoptee, Donor Conceived, NPE, and MPE Community. Host of the popular podcast Everything’s Relative with Eve Sturges and an NPE (not parent expected) herself, she’s deeply familiar with the many ways the revelation of family secrets can sideline a person. It’s not a substitute for therapy, nor was it intended to be, but this first-of-its-kind journal is just the tool many need to help them on this unexpected journey; and for those who are in therapy, it can play a role, helping them think about their reactions and improving their ability to articulate their feelings. Sturges doesn’t provide answers. Instead, she offers prompts to stimulate your thoughts and kickstart self-expression. She asks questions and provides a safe space in which you can explore the answers, either privately, within a group, or with a therapist. Deceptively simple, it’s a crucial resource that’s certain to make a difference for thousands of NPEs and MPEs.

BKJ