Imagine yourself in this scenario. You tell your 92-year-old father that you want to take a DNA test to learn more about your heritage. Your father says, “I don’t want you to take that test until after I’m dead!” You ask why, and he can’t or won’t tell you. What do you do? Naturally, you take the test, and your father says, “Fine, piss on my wish,” and you spend weeks waiting for the results and wondering what’s the big mystery.

That’s what happened to Jon Baime when he was 54-years old. You might think he shouldn’t have been surprised to learn that the man he believed to be his father wasn’t related in any way, that he was in fact donor conceived, that his parents had been keeping a secret from him, about him. But even if you were raised in a family that keeps secrets, as he was, where children were often told that certain matters were none of their business—and even if you’ve always known that something in your family wasn’t quite adding up—it’s always a shock to find out your identity is not what you’ve always believed it to be, that your relationships changed in the moment you received your test results, that your whole world flipped upside down and there’s suddenly so much you don’t know that your head spins.

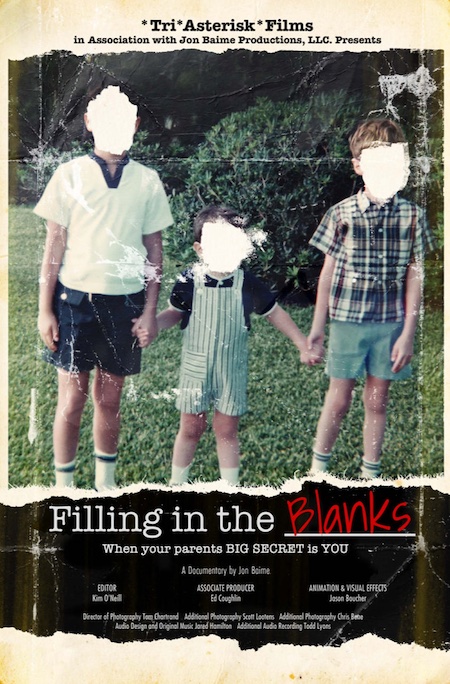

Throughout his “charmed childhood” in South Orange, New Jersey, with a moody accountant father and an outgoing mother, Baime, along with his two brothers, Eric and David, was told not to ask too many questions. After getting the results of his 23andMe test, however, he does nothing but ask questions. Who was his biological father, and was he alive? Were his brothers also donor-conceived? Did they have the same father? Why did no one tell them? Who else knew? What else didn’t they know? Should he tell his dad?

What do you do? How do you make sense of it? If you’re Baime, you call a therapist immediately and then you pick up your video camera.

He did what comes naturally to him. He documented his search for answers to an unspooling list of questions. His entire professional life had prepared him for the task. An Atlanta-based producer with a specialty in non-fiction projects, he began his career in television, producing a children’s show for CNN and producing and editing a documentary series for TBS about climate change and population issues, narrated by Jane Fonda. Later, as an independent producer, he worked on training videos for the CDC, web videos for the National Science Foundation, and segments of a PBS program about environmental issues.

During the four years after his DNA surprise, he used his professional skills to unravel the family’s secrets and lies—researching and scrambling through a trove of family history in the form of photos and home movies, and traveling the country to interview his brothers, his new siblings who appeared as DNA matches, a psychologist who studies new family ties, and, ultimately, his biological father. Along the way, Baime, who is charming, guileless, and immensely likable, has seemingly effortless and amiable conversations with his welcoming and enthusiastically cooperative new family members. The result is an engaging and enormously moving documentary that’s both surprisingly humorous and at the same time darkly unsettling. Baime doesn’t pretend to offer a generalized view of the experience of discovering that one was donor conceived. Certainly, many who make such a discovery may never be able to determine who their biological fathers were, let alone be embraced by them in the way Baime was. His brothers, in fact, weren’t. Baime offers only his singular experience, which is deeply affecting. He shares hard-won insight into what it’s like to have had the family rug pulled out from under him, to struggle with unknowns, and to journey from chaos and anger to peace and forgiveness.

Filling in the Blanks has been released to view on demand on multiple outlets, including Prime Video and Apple TV+.

Here, Baime talks with Severance about his experience and the making of the documentary.

It seems you conceived the idea of making a documentary—or at least documenting the unraveling of your story—quite early in the process. When did that happen and why? What compelled you to record your experience in this way?

What compelled me was that I spent a decades long career documenting non-fiction. Working at CNN, The National Science Foundation, and on a travel series called Small Town Big Deal, all gave me the foundation for nonfiction storytelling. Then, as it turns, out my parents had tons of eight and 16 millimeter films starting with their honeymoon and going straight through my adolescence. In addition, there were thousands of still photos. So I combined my knowledge of storytelling with hundreds of hours of footage and photos and created the documentary.

Your film overwhelmingly is about secrecy. You and the individuals you interview, your brothers and sisters, their mothers, your biofather, all appear remarkably at ease telling their stories, at ease with each other. Was there any reluctance initially? Did you have to persuade anyone to be involved, to spill their secrets or the secrets that were kept from them? Was there anyone who didn’t want you to tell this story?

Surprisingly, upon reflection, my biggest challenge in making the film wasn’t anyone’s reluctance to do it. It was scheduling around bouts of COVID-19. But as it turns out, I had very little resistance from anyone in the film to participate. I have to admit when I first started asking people I was a little skittish. However, by the time I was done with the filming, I was pleasantly surprised by how many people agreed to participate with little or no pushback. If I only had that luck with last week’s mega-millions jackpot!

You talk about your habit of snooping through drawers, boxes, closets—a scavenger hunt you called it, as if you knew there was something to be found, something you didn’t know. It reminded me of what Dani Shapiro wrote in Inheritance that speaks to what she calls—using an expression from the psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas—the “unthought known.” There are a number of ways that expression is defined. I think of it like this. I refer to my father as the king of denial. Forced to face some deeply difficult truth or discovery, he’d say “I knew but didn’t know,” which I interpreted as him saying there were truths deeply buried or even hiding in plain sight that he couldn’t think about, couldn’t consciously recognize, but nonetheless were present deep down, greatly affecting him. At an early point in the film, you say so much was good about your life, yet something didn’t add up. It’s a feeling echoed by some of your newly discovered siblings. And upon making your discovery—and them making theirs—there seems to be an almost universal sense of things now making sense that hadn’t made sense before. Can you explain your sense that things didn’t add up? Was it always present?

There’s an old saying from my childhood: “Children should be seen but not heard.” But as I state in the movie, there’s something beyond that. When being around other families, their parents seemed more open about certain things. When we wanted to talk to our parents about things, often the response was, “These are things children should not know about.” At one point, one of my friend’s parents was terminally ill. When I asked my mother what was wrong with my friend’s mother, she would just say, “It’s not something children should hear about.” They were very controlling about revealing information. They often acted like telling us or sharing things with us was difficult. They spoke with us as if so many subjects were “classified” or “top secret.” Upon reflection, that kind of a boundary is difficult for a kid. It definitely reflects the kind of relationship the parents we’re trying to enable.

Although anger is mentioned occasionally—at one point you say you’re feeling angrier and angrier—but as I watched the film, I was struck and surprised by the lack of comment about anger by any of the participants. There’s a great deal of humor and even light-heartedness in much of the conversation. Yet at the end of the film, in a letter to your parents you refer to your “fury.” You say, “How dare you?” Can you talk about what part anger played in your experience and whether it’s something that became more acute over time?

I would say that the anger I experienced from this whole situation started the night I discovered I was donor conceived. The anger probably peaked two to three months after the discovery. Then the feelings of anger slowly dissipated over the next year or so. As I processed the situation, I think I used humor as a healing device. By the end of the film I am forgiving my parents for making what I think was a bad choice. I am forgiving myself for getting as angry as I did at them for the few months after I found out that I was donor conceived. Full disclosure, sometimes I still get a little angry about it. But I think it’s more along the lines of sometimes people remember things their parents did and they kind of roll their eyes. That’s where I am with this at this point.

At one point early on you observed that it was shattering to wonder “Who am I?” To wonder who was the other half? Perhaps it’s changed, but at the time of the making of the film, your two brothers hadn’t connected with their birth fathers. How do you think the experience was different for them than for you, never having that big piece of the puzzle? Can you—do you—imagine how different this experience might have been had you never been able to know your biological father or at least know who he was?

Let me start by answering this one brother at a time. With Eric, he was never particularly close with the father that raised us. It wasn’t hatred by any means, but they weren’t that close and often butted heads. So when Eric found out he was not related to the man that raised him, he was relieved. Also, Eric not knowing who his biological father is doesn’t seem to bother him all that much. David, on the other hand, claims that this whole situation does not bother him. David would have to speak for himself on this. I can tell you David’s biological father knows he has donor children who would like to meet him. But currently he is rejecting them and has no interest in meeting them. When I asked David how he feels about it, he says, “I don’t really care because I already have a father. So I don’t necessarily want to meet this other man.” If it were me, it’s hard to imagine how I’d feel. I remember the first few days before I discovered who my biological father was. And there is definitely a sense of what I could best describe as identity loss. I would hope that I would be able to process the situation and eventually come to terms with it.

For some time, you and your brother Eric decide to wait to share the news of your discoveries with your brother David. Later, after you’ve revealed what you’ve learned, he tells you it doesn’t bother him, as you just mentioned. Your reaction—your facial expression—suggested skepticism or perhaps just surprise. What was going through your mind in that moment?

It was, and sometimes still is, difficult for me to relate to David’s muted reaction—well, muted compared to mine. And even to this day, we go back and forth about how he could not have more emotion about the fact that we were donor conceived having been hidden from us by our parents.

For many people, discovering that they were donor conceived—discovering that the manner of their conception had been a secret to them, that others may have known, that they had no idea who their biological fathers were—is deeply traumatic. In your story I see shock and confusion, but not any sense of trauma. And yet, almost immediately you called a therapist. Had you recognized that you were on a precipice? That trauma was a possible outcome? How important was it for you to seek help? How much difference did that make for you?

I’m usually pretty good at handling more serious emotional issues. But this felt different. The concept of not being the biological son of the man who raised me was very hard to wrap my head around, especially when I was led to believe otherwise. I think it stems from something as simple as the fact (at least I believe) everyone has an origin story. Your origin story is as innate to you as what hand you write with, the color of your hair, or even your sexual orientation. It’s just very much a part of who you are and you might not give it much thought. And to find out that your origin story has been completely wrong for nearly 55 years is a shock. And you give it a lot of thought. But this was so far off the rails, so much of a curveball that life had thrown at me, that I never heard of anything like this before, I felt compelled to seek help.

How important to one’s identity, one’s sense of personal integrity, is it to acknowledge one’s truth, to pull the veil on what’s been kept secret?

This goes back to the origin story I was discussing in the last question. Your origin story is so important, but most people never think about it because they don’t have to. But when you have to think about it and completely rewrite it, then it can be emotionally exhausting.

How important is forgiveness in your story? You’ve said the story “is a voyage that seeks out a place of forgiveness from a place of anger.” Is the anger chiefly about the secrecy, and is the forgiveness extended for having been a secret? Or was there more to be angry about, more to be forgiven?

I think much of the anger came from the fact that my parents agreed to be deceptive about something they would never be able to deal with if they were in our situation. I just can’t imagine how my mother would have reacted if her mother said, “Harriet there’s something I need to tell you about your father.” The same goes for my dad. He would demand respect. I’m not sure why he felt that way because we were pretty good kids. I think sometimes he had doubts about whether he could love us the way he might have actually loved children he could have conceived himself. And sometimes he would project that on us. So it’s not just about the secrecy, it’s about the boundaries they put up because we weren’t born the way they might have liked us to have been born. And in some sense I think their way of expressing blame might have been to add an uneasy distance in our relationships. I need to be clear that I do believe both my parents loved all three of us. But I believe sometimes they weren’t completely at ease with the way we came into the world.

When you met your biological father, you asked an interesting question. “What do you want to give us?” Now that it’s done, what do you feel this film has given you? How has it changed you?

In addition to regular therapy, making the film is a kind of a cathartic experience. And in a way I sometimes wonder if I made the film or if the film made me who I am now. I do believe it’s changed me because the film is something that’s very much born out of me. I created it, I own it, and it’s my story to tell. Knowing that I have created something like this has given me an extra sense of self-confidence I never had. And it feels pretty damn good.

What do you hope it will give others?

The first thing I hope is that it makes people smile. Especially people who are donor conceived and have a tough time smiling when they think about it. Everyone’s story is different. I hope that when people watch this they might be able to find some kind of a silver lining in their own journey. I believe there’s a silver lining in almost every story—no matter how dark.